There’s a Reason This Bull Market Feels So Weird

We are now more than a year from the bear-market low of October 2022, and while the bull market isn’t exactly raging, stocks are still up more than 20%. The markets, though, aren’t behaving as they usually do at the start of long-lasting bull markets. In some respects, the past year looks more like the tail end of one than the beginning. This makes me worry it may not last.

Here’s the basic outline of what happens in the first year of a bull market, using the lows of October 1990, October 2002, March 2009 and March 2020 as a template: Everything goes up. That is pretty much it. At the start of the past four bull markets, the rebound was led by banks and smaller companies. And in three out of the four bull markets, earnings forecasts rose, too. But investors took a simplistic approach to bullishness and bought almost everything. It was hard to lose money on stocks.

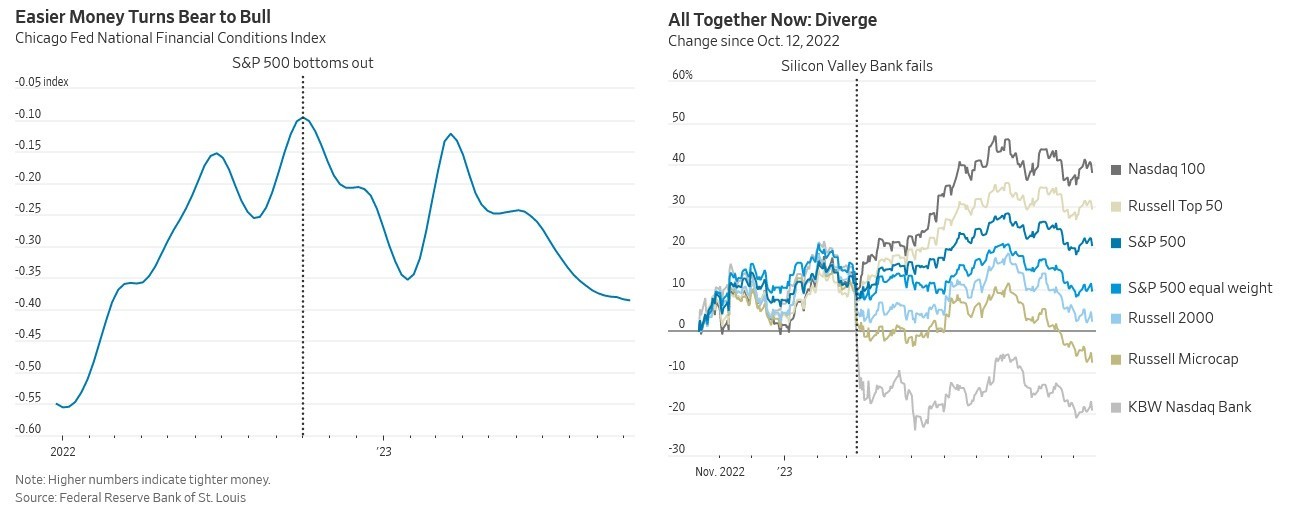

This time, large numbers of stocks went down, even as the S&P 500 went up. Banks did badly, and smaller companies worse, while earnings expectations have dropped. This isn’t normal. A few examples: Only two-thirds of members of the S&P rose over the 12 months, compared with 88%-97% in the first 12 months of the past four bull markets, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices.

The smallest companies missed out on the gains entirely. The Russell Microcap index of the smallest 1,500 or so stocks is down, continuing last year’s bear market. The Russell 2000 has gyrated but on Friday was roughly unchanged from the October closing low. Even within big stocks the concentration of gains in the very biggest has been extraordinary. Half the gains in the S&P came from just eight stocks; in the first year of the four previous bull markets it took at least 38 stocks to get to half the gains.

The concentration of gains among the biggest stocks is one of three features that distinguish this bull, and is something that typically happens at the end of bull markets, not the start. Bull markets are often defined as when stocks go up 20%, and the S&P is now up less than 20% from its closing low in October last year—but much further above the intraday low. Look past technical definitions, though, as a real bull market is more than just stocks rising for a bit. In a bull market, they should trend upward over multiple years, as they did from 1990 to 2000, 2002 to 2007, 2009 to 2020, and 2020 to 2022, with only brief and relatively shallow drops.

If this latest bull market peters out, it could turn out to be nothing more than a very large bounce amid the bear market that began at the start of last year.

Silicon Valley Bank fails. The other two features are intertwined: poor bank performance and the lack of a recession from which to recover. In the first year of all four previous bull markets, banks led the market up, as investors anticipated the end of the recession which had previously hurt bank stocks.

This time banks just kept on falling. They had another bad year to follow last year’s plunge. Rising bond yields turned into a bank run at Silicon Valley Bank and others. This bank run marked the point of divergence. From October 2022 until March, U.S. stocks were joined at the hip, with virtually identical performance from tiny, small and large stocks, from Big Tech and from banks. Maybe it was a bull market, maybe a dead-cat bounce, but either way investors were indiscriminate in their buying as fears of recession abated. After SVB’s failure, performance split. Big Tech soared as AI excitement took hold and their cash piles made them look secure. Banks and smaller stocks plummeted, and the average S&P 500 stock went sideways.

Now, just because the bull market isn’t like past recent bull markets doesn’t mean it won’t last. Russell Napier, keeper of the Library of Mistakes in Edinburgh and author of “Anatomy of the Bear: Lessons From Wall Street’s Four Great Bottoms,” says this bull market is really about state and central-bank support. Stocks reached their low in the autumn when overleveraged British pension funds neared collapse because of a leap in bond yields sparked by the government’s short-lived plan for unfunded tax cuts. The Bank of England stepped in with support, while the Swiss National Bank borrowed billions of dollars from the Federal Reserve at the same time to supply to its banks (Credit Suisse eventually failed anyway). Then from March onward, the Fed directly lent more than $100 billion to domestic banks on easy terms to try to prevent further bank runs.

The “Fed put” was back, kinda. “The socialization of risk is what’s going on here,” Napier says. “That drives up your long-term interest-rate risk but reduces private-sector credit risk.” I’m not convinced this explains the strange structure of the bull market. When the government takes on credit risk, it ought to be best for the riskier borrowers and for lenders. But the winners have instead been huge tech companies sitting on large cash piles.

Perhaps former British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s explanation of why things happen best suits the past year: “Events, dear boy, events.” The low in the autumn resulted from the twin fears of recession and financial crisis, which went away as the economy kept growing and central banks offered support. Then in March the new bank crisis and AI excitement drove market divergence, and it just happens that the AI winners are so big that their gains lifted the S&P.

On Napier’s view, investors should be buying the firms that benefit from the new government handouts—sorry, industrial policy—and selling those that will be crowded out by the higher loan costs that result from much more government borrowing. If the October extreme and subsequent rebound results just from a series of unfortunate events, each event needs its own analysis. Will AI live up to the hype? How badly will banks and smaller companies be hit by higher rates? Will the economy eventually suffer from higher rates? Either way, the past year doesn’t fit the standard pattern for a new bull market, which ought to give optimists pause for thought.