Rising Loan Costs Are Hurting Riskier Companies

Investors fear unsustainably high interest rates will spark bank-loan defaults. Petco executives say they are concentrating on relieving interest-rate woe. Petco took out a $1.7 billion loan two years ago at an interest rate around 3.5%. Now it pays almost 9%. Interest costs for the pet-products retailer surged to nearly a quarter of free cash flow in this year’s second quarter. Early in 2021, when Petco borrowed the money, those costs were less than 5% of cash flow. Now, executives say easing that burden is a company priority. Debt reduction is one of Petco’s three key capital-allocation initiatives, Chairman Ronald Coughlin said on the company’s August earnings call.

Petco isn’t alone. Many companies borrowed at ultralow rates during the pandemic through so-called leveraged loans. Often used to fund private-equity buyouts—or by companies with low credit ratings—this debt has payments that adjust with the short-term rates recently lifted by the Federal Reserve. Now, interest costs in the $1.7 trillion market are biting and Fed officials are forecasting that they will stay high for some time.

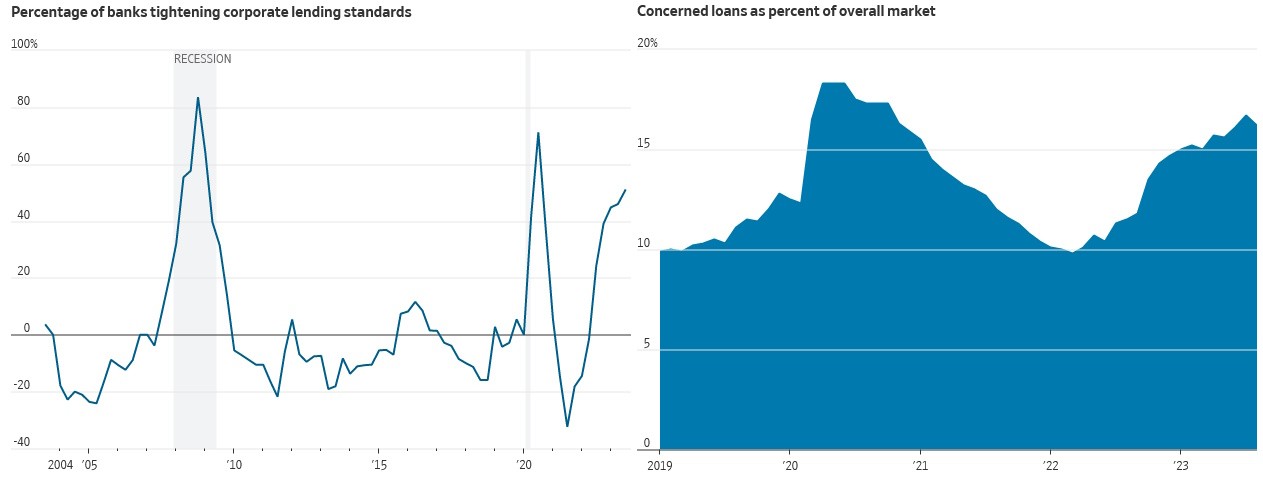

Nearly $270 billion of leveraged loans carry weak credit profiles and are potentially at risk of default, according to ratings firm Fitch. Conditions have deteriorated as the Fed has raised rates, beginning to show signs of stress not seen since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Excluding a 2020 spike, the default rate for the past 12 months is the highest since 2014. The strains come at a time when leveraged-loan funds have put up outsize performances. Investors had feared rising rates would hurt risky borrowers, particularly if they spark a recession. Instead, a strong economy has helped issuers withstand rising interest costs while bonds with low fixed rates have tumbled, amplifying the advantage of floating-rate debt.

James St. Aubin, chief investment officer at Sierra Mutual Funds, said leveraged loans’ gains could easily unravel if the Fed’s tightening campaign breaks something in the economy and kicks off a wave of defaults. Sierra owns floating-rate debt in its Tactical All Asset Fund, which uses algorithmic models to buy and sell assets based on how well they are doing. “The asset I’m worried about most is bank loans,” he said.

Hanesbrands has nearly $1.9 billion outstanding across two bank loans, paying rates between 7.2% and 8.9%. The apparel maker is trying to improve leverage—its debt relative to earnings—and lower interest costs by using “all our free cash flow to pay down debt,” Scott Lewis, chief financial officer, said in August. The company has made progress, paying down $100 million of debt in the first half of the year and looking to do an additional $300 million in the back half. But cash flows have only outpaced interest expenses in two of the past six reported quarters. In the most recent period, $75 million of interest costs gobbled up nearly the entire $78 million of free cash flow. S&P downgraded Hanesbrands last month to B-plus from double-B minus. Moody’s in June reduced Petco’s rating further into speculative territory, to B2 from B1. Petco has paid down a portion of its debt as well, and hedged some of its interest-rate risk as the Fed raised rates.

One sign of hope for investors and companies is that CFOs and Wall Street analysts are growing more confident that the economy can skirt a recession. They see healthy consumer spending, propped up by the resilient labor market, allowing for revenue growth. That cash can be used to pay down high-rate debt. “So far, borrowers have done a good job of managing increased interest costs as the economy has held up better than many expected at the start of the year,” said Hussein Adatia, who manages portfolios of stressed and distressed corporate credit for Dallas-based Westwood. “The No. 1 risk to leveraged loans is if we get a big slowdown in the economy.”

That would pose additional challenges for issuers such as Hanesbrands or Petco. Americans are already buying fewer pets, and Hanesbrands recently announced it is shopping its Champion business amid an activist-investor campaign against management. According to the Fed’s senior-loan-officer survey, banks are becoming more stringent about whom they are willing to lend to, making it more difficult for low-rated companies to refinance. Fitch expects about $61 billion of those loans to default in the next two years, the “overwhelmingly majority of which” are anticipated by the end of 2023.

Some investors worry that tighter standards come too late. Years of ultralow rates left investors thirsty for yield and handed borrowers favorable terms. Historically, creditors have recovered about two-thirds of their initial loans during defaults, according to Adatia, but he expects that will be much lower now. “The overall quality of loan documents is atrocious right now,” he said. “This is 15 years in the making.”