What is Behind the Stock Market Rally This Year

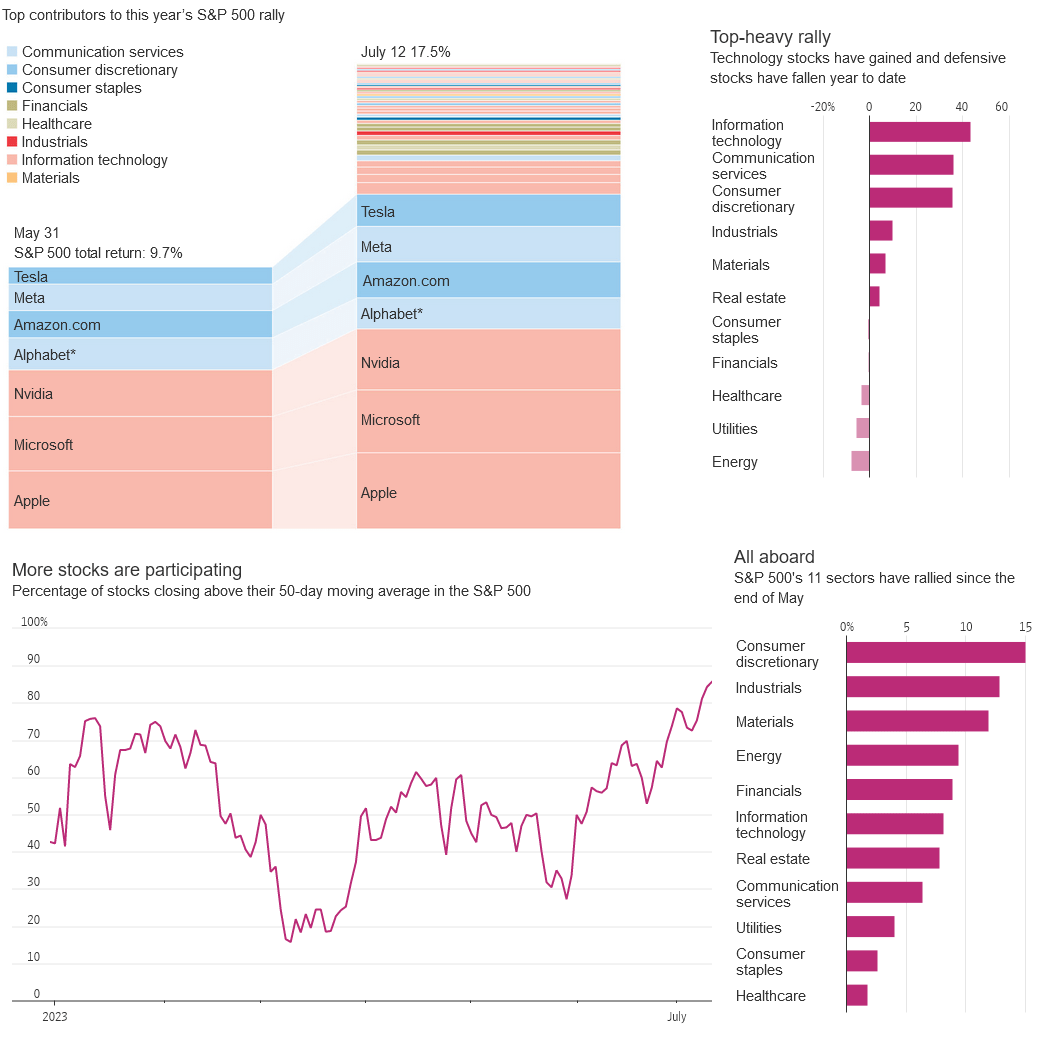

The stock market rally is no longer just a big-tech rally. Just a couple months ago, the seven largest tech companies in the U.S. were responsible for virtually all of the stock market’s 2023 gains. Eye-popping returns from shares of companies like Apple, Microsoft and Nvidia propelled the S&P 500 into a new bull market. The tech behemoths became so dominant that they earned a fresh moniker: the “Magnificent Seven.”

Now, shares of many companies are making the rally broader. More than 140 stocks in the index have hit fresh 52-week highs since the end of May, such as Lowe’s and General Electric. All 11 sectors of the S&P 500 have climbed during that period, pushing the index up more than 17% for the year. Small-cap stocks are rising, too. It would now take wiping out the gains of the top 50 stocks in the S&P 500—including Visa, McDonald’s and FedEx—to negate the index’s rally this year, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices data as of Wednesday.

Wall Street often views improving breadth as a measure of health in the stock market and an omen that the rally could last. It has given more investors confidence to flock to stocks, despite lingering concerns about slowing corporate profits, the potential of a recession and the Federal Reserve’s ongoing campaign to tame inflation through interest-rate increases. “The market is sending a very powerful signal with this broadening out,” said Andrew Slimmon, senior portfolio manager at Morgan Stanley Investment Management. “I think we’re going to have this continued rally.” Slimmon said he is looking for buying opportunities in areas that have lagged behind the broader market this year, such as shares of some financial companies.

The U.S. economy has proved to be more resilient than expected: The labor market has remained robust, consumers are opening their wallets and panic about the banking sector has subsided. Investors came into 2023 weary of stocks after last year’s bruising losses. But as inflation showed signs of moderating and some investors bet the Fed would soon pause or reverse its interest-rate lifts, stocks mounted a comeback. Then the rapid collapse of venture capital-focused Silicon Valley Bank in March and ensuing turmoil in the financial system turned shares of big, established tech companies into a safe haven while other areas of the market reeled. A frenzy around developments in artificial intelligence pushed the big tech stocks even higher through the spring. The market value of the Magnificent Seven—Alphabet, Amazon.com, Apple, Meta Platforms, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla—swelled. Nvidia shares popped 31% over just three trading sessions in May.

The S&P 500, which is weighted by market capitalization, reaped the benefits of tech’s rise. Under the surface, though, performance was rocky. The equal-weighted S&P 500, which gives the same status to the smallest and largest companies in the index, was down about 1% for the year at the end of May. Tight market leadership tends to make investors nervous. The outsize influence of just a handful of large companies in the S&P 500 makes the broad index vulnerable to a downturn if a few heavyweights drop. Just six weeks ago, the S&P 500 would have been negative year-to-date without the contributions of the Magnificent Seven, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices.

“Whenever there is a narrow market participation, that leads to a bubble,” said Venkat Balakrishnan, head of asset allocation at MissionSquare Retirement. “The bubble is going to break and that is not good for the market.”

That is why the turning point in market breadth has given ammunition to the bulls. A widely followed technical indicator for market breadth this past week hit a level not seen since last year. The share of S&P 500 stocks closing above their 50-day moving averages surpassed 80% for the first time since December 2022, according to FactSet. The equal-weighted S&P 500 has outperformed the cap-weighted S&P 500 over the past six weeks as well.

Balakrishnan said his firm is planning to buy more value stocks—shares trading at prices perceived to be relatively cheap for their returns—as the rally expands. “For diversified portfolios, this is a good thing. You don’t have to depend on one scoop of highly concentrated U.S. growth stocks,” he said. Maggi Keating, senior portfolio manager at FBB Capital Partners, said her firm owns five of the Magnificent Seven stocks, but isn’t planning to chase the tech rally further by adding to the holdings. She said she is remaining fully invested across all sectors of the market. “It’s just healthier for the market in general to have all companies in all sectors participate, rather than just a handful,” Keating said.

Individual investors are increasingly putting more money into exchange-traded funds tracking broad indexes, according to Vanda Research. Net inflows from individuals into the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust surged going into July and remain elevated versus last year’s levels. “There seems to be growing conviction in the market,” said Marco Iachini, Vanda’s senior vice president of research. Mark Schmitt, 59, said he added about $150,000 to the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF in the past month and recently moved roughly $50,000 out of a real estate ETF to put into a broader index fund. He prefers investing in broad funds rather than selecting individual stocks. “I’m bullish and expect the market to continue going up,” said Schmitt, an executive in medical-device manufacturing based in Atwater, Minn.

Behind the renewed optimism in stocks is a growing hope in a soft landing for the economy—a scenario in which the Fed gets inflation under control without triggering a recession. The latest data on consumer prices showed inflation eased in June to its lowest level since early 2021. Hiring also slowed in June but unemployment remained historically low. The U.S. economy is still growing, according to recent estimates.

“We’re in this Goldilocks economy,” said Jay Hatfield, chief executive at Infrastructure Capital Management. Many traders are betting the easing inflation data could put the Fed on track to stop lifting rates after its policy meeting later this month, potentially ending the most aggressive rate-raising campaign since the 1980s.

Some market participants say they believe stocks have more room to run as investors with money on the sidelines develop a fear of missing out and chase the rally. Investors have pulled out around $90 billion from stock mutual funds and ETFs on a net basis since the beginning of the year, according to Refinitiv Lipper, a sign that more money could come back into the stock market.

Scott Ladner, chief investment officer at Horizon Investments, said his firm has held an outsize position in tech and consumer-discretionary stocks for most of the year but is beginning to rotate into other sectors. He thinks the S&P 500 could finish the year 5% to 7% higher from here. “It’s probably time for more cyclical parts of the stock market to pick up the load,” he said, referring to shares of materials and energy companies, which his firm is starting to buy. “When you have such significant outperformance by a small handful of stocks and such significant underperformance by the rest of the market, it brings opportunities,” said Liz Ann Sonders, chief investment strategist at Charles Schwab.

Doug Kelly, portfolio manager at William Jones Wealth Management, first started investing in the early 1980s when International Business Machines and AT&T made up a huge share of the S&P 500. He said meaningful market breadth is necessary for a strong rally. “For me, the more steady broadening out is what we hope for,” Kelly said. “You can’t have trillion-dollar stocks double every six months. That’s just not going to happen.” Kelly said he recently bought stocks outside of tech, snapping up home-improvement-company shares as the U.S. housing supply remains tight.

Pessimists have their pick of reasons to doubt the rebound. Some investors worry market consensus could be wrong about soft-landing bets or the Fed’s interest-rate plans. “Every step along the way for the past year and a half, the market has gotten some degree of complacency that the Fed was done or even reversing course. Those expectations have been repeatedly dashed,” said Yung-Yu Ma, chief investment officer at BMO Wealth Management.

The broader stock rally presents another challenge to the Fed. The wealth effect from stock-market gains can increase consumer spending, which, in turn, can boost corporate earnings and keep the economy churning. But spending can also add to inflation, putting pressure on the Fed to keep raising rates. Market sentiment has swung from one extreme to the other this year. Investors in early July were the most optimistic about stocks since 2021, according to the American Association of Individual Investors survey. But, sentiment is often considered a contrarian indicator, meaning that when the crowd feels heavily one way, some investors see it as a signal to do the opposite.

Stocks also look pricey relative to history after this year’s run-up. Investors often use the ratio of price to earnings as a gauge for whether stocks appear cheap or expensive. Companies in the S&P 500 are trading at about 19 times their projected earnings over the next 12 months, up from a multiple of roughly 17 at the beginning of the year and above the five-year average of 18.6. The information technology sector has a multiple of about 27.