Fed Official Is Open to Forgoing June Rate Hike

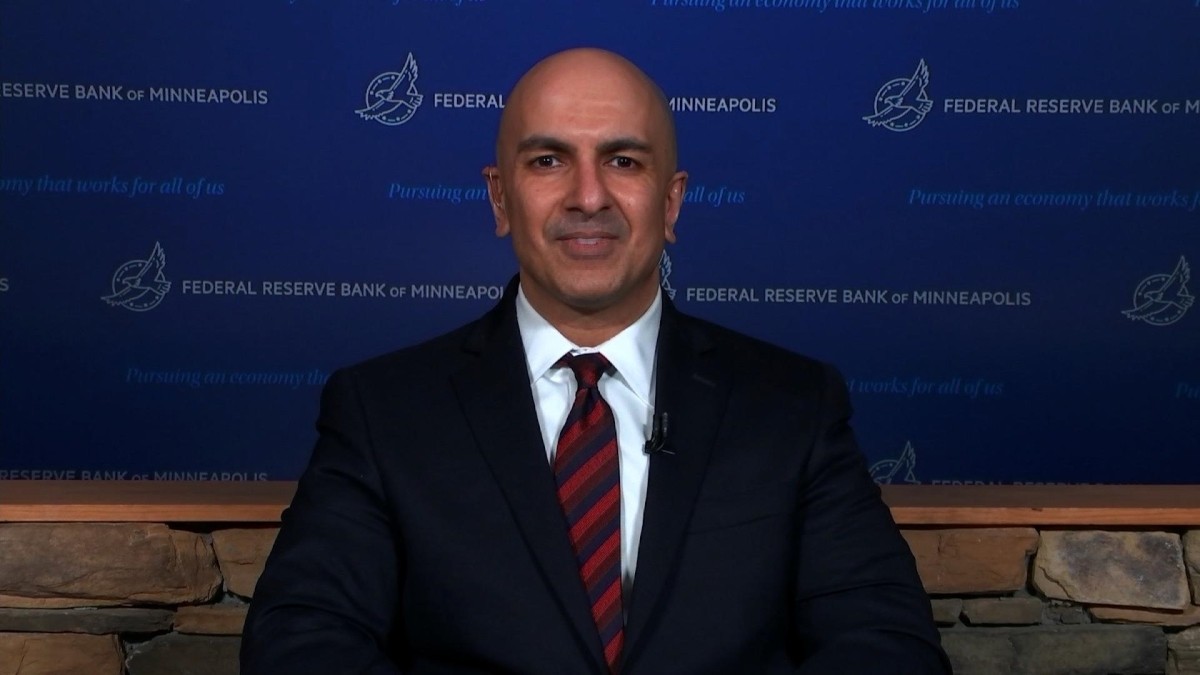

Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari said he could support holding interest rates steady at the central bank’s next meeting to give officials more time to assess the effects of past rate increases and the inflation outlook. “I’m open to the idea that we can move a little bit more slowly from here,” he said in an interview Friday. The Fed has raised its benchmark federal-funds rate rapidly over the past year to fight inflation, most recently this month to a range between 5% and 5.25%, a 16-year high.

Officials have indicated that their decision on whether to raise rates at their June 13-14 policy meeting could be a close call. A handful have said inflation and economic activity aren’t slowing enough to justify leaving rates unchanged. But others, including Fed Chair Jerome Powell, have hinted that they might skip a rate rise to better study the potentially lagged effects of the rapid rate increases. “I would object to any kind of declaration that we’re done. If the committee chooses to skip a meeting because we want to get more information, I could make the argument why that makes sense,” Kashkari said. “A skip to get more information is very different in my mind than [saying], ‘Hey, we think we’re done.’”

Kashkari said he was sensitive to the delayed impact of the Fed’s rapid rate increases and to a potential credit crunch from higher bank-funding costs that resulted from the failure of three midsize lenders since March. In addition, while inflation wasn’t declining as quickly as officials had hoped, “it does seem to be coming down,” Kashkari said. “It is at least not getting worse. And then you add the uncertainties about the banking sector, and are the stresses really behind us? Are there more stresses yet to emerge? I think that does give us some reason to say, ‘Hey, let’s go a little bit slower.’”

Before the pandemic, Kashkari was one of the most dovish members of the Fed’s rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee, consistently favoring easier monetary policy. But last year, he became one of the committee’s more outspoken inflation hawks—those generally favoring tighter policy. He is a voting member of the FOMC this year. Indeed, Kashkari said he was sympathetic to arguments for continuing to raise interest rates because inflation has been higher for longer than officials expected. “The cost of not getting inflation down to 2% is much higher to Main Street than the cost of getting it down to 2%,” he said. “So I would rather err on being a little bit more hawkish rather than regretting it and having been too dovish.”

Kashkari said he wasn’t seeing evidence of a credit contraction in his Fed district, which includes Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and parts of Wisconsin and Michigan. But his experience as a senior Treasury Department official during the 2008 financial crisis made him humble enough to recognize “these banking stresses are not necessarily completely behind us,” he said. “And it could be that when those stresses emerge, those become serious enough that they actually put a meaningful damper on economic activity.”

Banks are facing losses on fixed-rate securities they acquired when interest rates were at very low levels in 2021, though they don’t have to recognize cash losses if the underwater investments are held to maturity. The inverted yield curve, in which yields are higher on short-term debt than long-term bonds, can crimp banks’ ability to lend at a profit. “There’s no question an inverted yield curve doesn’t work for banks. It violates the fundamentals of their business models, and the longer it’s inverted, the more challenging the environment becomes for banks,” said Kashkari.

Just how serious those stresses become are linked to the outlook for inflation, said Kashkari. If inflation slows quickly, the Fed might be able to lower interest rates early next year, which would relieve pressure on the banks. If high inflation is more persistent, however, and requires the Fed to hold rates at higher levels for longer or to continue raising them, then banking sector stresses “probably become more serious,” he said.