The principles of the global order are under scrutiny

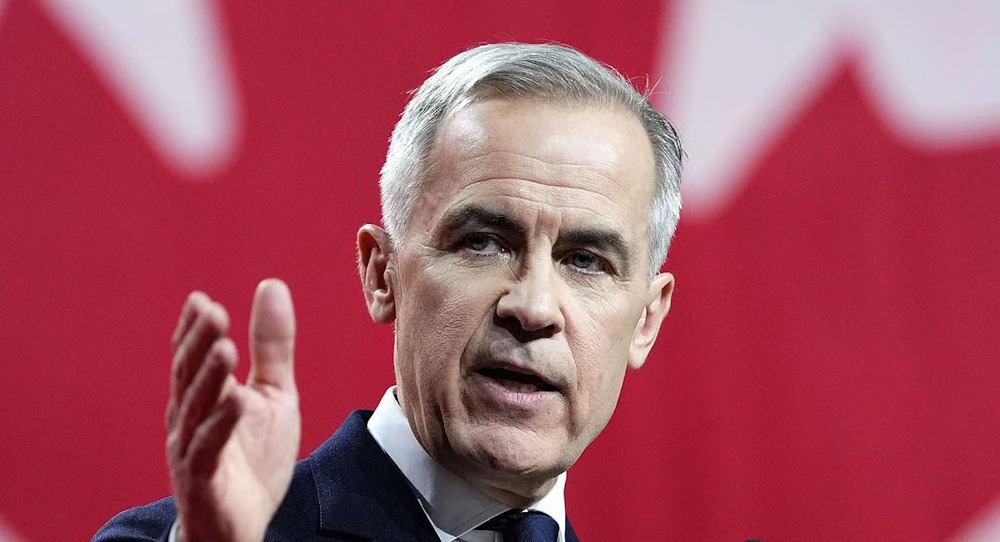

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney recently characterized the rules-based international order, a concept that emerged after World War II, as “partially false” and, in many respects, a “fiction.” He contended that the world’s most powerful states have frequently exempted themselves from obligations “when convenient” and that international law was “applied with varying rigour depending on the identity of the accused or the victim.” Moreover, he is not the only one who has expressed this unexpectedly. The phrase ‘rules-based order under collapse’ has been prominently featured in policy papers, political speeches, and diplomatic discussions for quite a while now. The shift first emerged during Donald Trump’s initial term as US president, when Washington openly scrutinized multilateral institutions and agreements. This trend has intensified since last year, when he assumed the White House for a second term and has aggressively pursued changes in trade, security, and alliances. What constitutes the rules-based international order, and what factors are contributing to its current strain? Prior to 1945, the landscape of international relations was characterized by empires, fluctuating alliances, and spheres of influence, accompanied by limited effective restrictions on the application of force. The League of Nations endeavored to establish collective regulations following World War I; however, it faltered because of its limited authority and the lack of participation from major powers.

The term “rules-based international order” emerged in the wake of the Second World War, primarily reflecting a consensus on a framework of international laws, agreements, norms, and institutions that would ultimately influence the interactions among nations. It did not establish binding legal obligations due to its inability to enforce compliance. Instead, it referred to a widely accepted framework centered on mutual expectations that borders would be honored, disputes would be settled through institutions rather than through force, trade would adhere to established rules, and power would be exercised within the constraints defined by international law. The agreement between nations depended on global institutions, particularly the United Nations and its Charter, which aimed to limit the use of force, acknowledge the sovereignty of states, and offer mechanisms for collective security. Over time, this framework expanded to encompass economic and legal institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and, later, the World Trade Organization, in addition to treaties that govern warfare, human rights, maritime law, and arms control. Together, while these arrangements or institutions did not eradicate conflict or inequality between nations, they succeeded in fostering a certain level of predictability in international relations. The formal foundations of the rules-based order were established in 1945, when representatives from over 50 nations convened in San Francisco to draft the United Nations Charter. The aftermath of two world wars and the disintegration of the League of Nations necessitated urgent actions to prevent a descent into the abyss of global conflict once more. The objective was not to eliminate power politics, but to manage it through legal frameworks, diplomatic efforts, and collaborative institutions.

For instance, global economic stability was tackled via the Bretton Woods system, which established regulations for international finance and trade and set up institutions designed to avert the monetary collapse and protectionism that exacerbated the Great Depression. Security arrangements were implemented, encompassing military alliances and confidence-building mechanisms aimed at deterring large-scale conflict, especially throughout the Cold War period. However, it is crucial to recognize that this framework developed in an uneven manner. New treaties were established, institutions broadened their mandates, and membership increased as former colonies transitioned into independent states. What emerged was often characterized as a liberal international order, not due to the prevalence of liberal democracies among states, but because the system prioritized open markets, legal norms, and institutionalized cooperation, with the United States occupying a central position as the dominant power. In recent years, the notion that the rules-based order is deteriorating has transitioned from scholarly discussion into the realm of mainstream political conversation. The intensity of geopolitical rivalry has escalated, compounded by the resurgence of competition among major powers, which has challenged the belief that disputes would be resolved within the framework of established rules. The invasion of Ukraine by Russia, along with China’s growing assertions in disputed maritime areas and the rising militarisation in various regions, has prompted a reevaluation of the strength of principles concerning sovereignty and non-aggression.

At the same time, shifts in domestic politics within key Western nations have dampened enthusiasm for multilateralism. Trade agreements, security commitments, and international institutions have increasingly been viewed as constraints rather than stabilizing mechanisms, resulting in more unilateral and transactional approaches, especially from the United States in recent years. As a result, the WTO is becoming less effective, with influential countries like the US crafting global trade policies that cater solely to their own interests. Critics have consistently contended that the principles governing the globalised, liberal world were never enforced uniformly. Time and again, powerful states have bypassed international law or institutions while insisting that others comply. This selective application, now more openly acknowledged by certain Western leaders, has diminished the credibility of assertions that the system is neutral or universally enforced. The system has been exposed in its inefficiencies, struggling to adapt to evolving challenges like cyber warfare, economic coercion, and climate change. International relations experts have noted a growing trend towards multipolarity, where multiple centres of power influence rules within their regions or through alternative groupings. While new institutions and alignments are taking shape, including BRICS and various free trade agreements, none have yet provided a thorough alternative. Consequently, should the rules-based order deteriorate without viable alternatives, the probable outcome will not be a void of rules, but rather a clash of disparate rules enforced inconsistently across various regions. This scenario will lead to heightened uncertainty in trade, security, and diplomacy, particularly affecting smaller states.