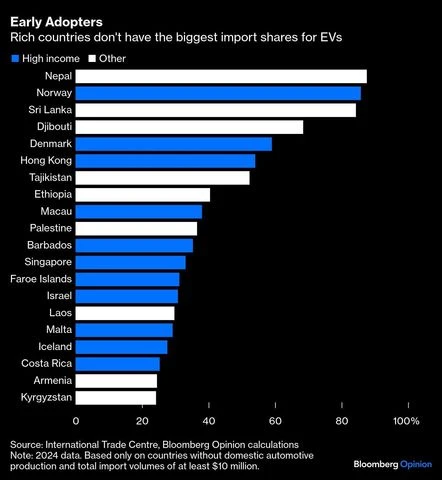

Developing nations adopt more EVs, contradicting oil demand narrative

There exists a narrative that proponents of oil often embrace to mitigate concerns regarding future prospects: Despite the fervor for electric vehicles among a select group in Europe and California, a vast number of drivers in the Global South are poised to drive the next surge in petroleum demand. Individuals holding this belief may wish to examine the current purchasing trends in automobiles and motorcycles among consumers. Developing nations are not lagging behind the affluent world in their enthusiasm for battery cars; rather, they are experiencing a significant surge forward.

China, which commands nearly half the market for plug-in vehicles, often captures the spotlight; however, neighboring Vietnam is not lagging significantly behind. VinFast Auto Ltd., a dedicated electric vehicle manufacturer, represented over one-third of automobile sales during the initial half of this year. According to a survey by Strategy&, Turkey’s 13 per cent sales share for fully electric vehicles in the first quarter was approximately double the penetration rate observed in Spain and Australia. In Indonesia, the proportion was approximately equivalent to that in the US, standing at 7.4 percent. In Malaysia, the growth rate was recorded at 8.6 percent during the first half of the year.

)

It implies a quick global move to electric transportation, like the Gulf oil states’ EV surge, making OPEC’s prediction of a 50% increase in developing nations’ oil use by 2050 seem impossible. Those nations continue to maintain established automotive sectors that are actively producing internal combustion engines. Dynamics are accelerating even more rapidly in countries that are entirely reliant on imports. Over 75% of the value of vehicles imported into Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Djibouti in the previous year was comprised solely of electric models. In Ethiopia, import shares stood at 40 percent, while in Laos, they accounted for 30 percent. According to the International Energy Agency, there was a notable increase of 60 per cent in plug-in sales across developing countries in 2024.

The emergence of electric vehicles in the Gulf’s oil-producing regions signifies a rapid transition towards electric mobility, reflecting broader trends in global energy consumption. The rapidity of the transformation renders the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries’ expectation of a 50% increase in oil consumption from developing economies by 2050 seemingly misguided. It is plausible that the pace of rapid electrification may experience a deceleration. In recent years, purchasers of electric vehicles in developing economies have benefited from various exemptions pertaining to import tariffs, licenses, and sales taxes. As local markets develop and reach maturity, the possibility of removing these subsidies arises.

)

That is a precarious foundation upon which to build expectations for a revival in gasoline demand, however. In significant emerging markets, battery electric vehicles reached price parity with traditional vehicles last year, with Thailand even witnessing lower prices for the former. Declining battery costs coupled with increasing production volumes have led to a further 10 percent reduction in the prices of leading Chinese electric vehicles. Additionally, a depreciating US dollar has enhanced purchasing power across various nations. When considering the reduced ownership expenses associated with electric vehicles, particularly in developing economies where a significant proportion of vehicles serve as taxis and for goods transportation rather than private use, it is reasonable to conclude that battery-powered automobiles will remain competitive with traditional vehicles, even in the absence of governmental assistance.

Policymakers are expected to prolong these incentives due to overarching macroeconomic considerations. In India and Pakistan, the contribution of oil and gas to the total import bill reaches approximately one-third, in stark contrast to the roughly 10 percent observed in the United States and the European Union. The economy exhibits a notable susceptibility to fluctuations in crude oil prices, which results in expenditures on transport fuel benefiting foreign nations instead of being reinvested within domestic supply chains, thereby limiting potential contributions to economic growth. Transitioning fifty percent of India’s automobile fleet to electric vehicles — an aspiration that remains distant, undoubtedly — could potentially resolve the nation’s ongoing current account deficit, as indicated by a study conducted in 2022.

)

Traditional vehicles will continue to consume gasoline for years following their removal from dealership inventories. We anticipate that the fleet of plug-free vehicles will not reach its peak until 2028. This will create a persistent demand for gasoline and diesel; however, it remains a diminishing market. By 2030, anticipations that electric vehicles will displace approximately 5.3 million barrels of oil per day, which represents around one-tenth of the total road fuel consumption worldwide at this time. The more compelling rationale for the robustness of road fuel at this juncture is not predicated on the assumption that emerging markets will significantly increase their consumption of it.

It is evident that this contest is currently being lost. Rather, it is the case that affluent nations have increased tariff barriers, mismanaged charger deployments, and relaxed fuel-economy regulations to such an extent that they have undermined their own transition strategies. This situation allows established car manufacturers to extend the lifespan of their outdated operations, while rivals in the Global South capitalize on the opportunity to gain a technological advantage. Most of the global economy is already capitalizing on cleaner, more cost-effective road transportation options. By the time advanced economies recognize the extent of their decline, it will be too late to recover.