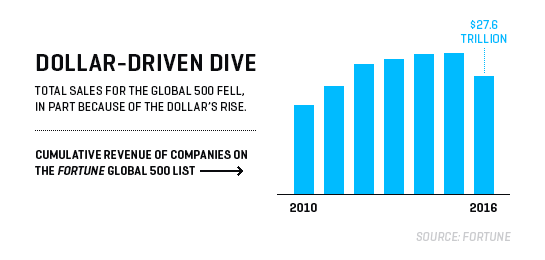

The world’s largest companies took a major step back over the past year. Cumulative sales of the Global 500—Fortune’s annual list of the biggest companies on the planet ranked by revenue, in dollars, for the previous fiscal year—declined for the first time since 2010. And not by a token amount either. Total revenue shrank from $ 31.2 trillion in fiscal 2014 to $ 27.6 trillion in 2015, or a fall of 11.5%. Profits dropped by 11.2%, to $ 1.48 trillion.

There are plenty of reasons for the reversal. A slowdown in China’s once-booming economy has affected companies worldwide. Growth in the U.S. and Europe remains modest at best. And sustained low oil prices have erased billions in sales for giant petroleum producers like Exxon Mobil xom , Royal Dutch Shell rds.a , and Sinopec.

But one macroeconomic trend looms largest of all: the explosive comeback of the U.S. dollar and the wide-ranging impact of its renewed strength on global trade.

Not long ago, the once-almighty greenback was out of fashion. From Beijing to Brussels, the prevailing wisdom held that a dollar-driven world no longer made sense, as some politicians and central bankers called for an end to its nearly 100-year hegemony as the world’s reserve currency.

But over the past two years much of the rhetoric has been forgotten, and investors have placed their bets on the dollar’s continued dominance. With chaos reigning in much of the world, the U.S. has reemerged as the planet’s pillar of economic strength and stability. The recent flight to dollars following the stunning Brexit vote—driving the pound to a 31-year low vs. its cross-Atlantic rival—underscored that when investors crave safety, money rushes to the U.S. and its sturdy currency.

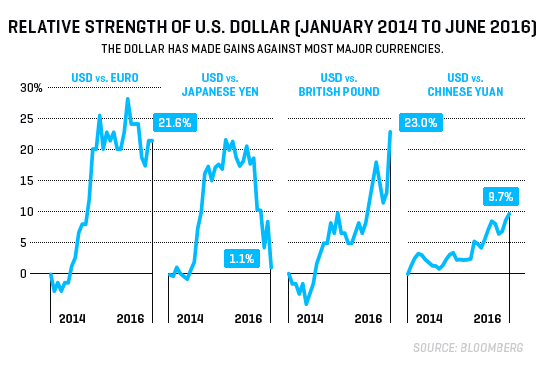

The numbers tell the story. From the middle of 2011 to the summer of 2014, the value of the dollar increased 9% vs. an index of the world’s major currencies, according to the Federal Reserve. But over the past two years the U.S. currency has rocketed up another 20%.

Traditionally, a strong dollar has been a badge of honor for America. However, economists warn that today the greenback’s large, sudden appreciation is proving to be a major drag on the U.S. economy that will get only heavier—especially as it is likely to last for years to come.

The dollar’s rise will swell the U.S. trade deficit and inflict a big hit on growth. It’s already hindering GM’s gm car sales in Europe, for example, and shrinking Deere’s tractor revenues in Asia. To lower prices and recoup sales abroad, experts predict, American manufacturers will seek to boost efficiency by shrinking workforces and investing in cost-saving technology.

“This isn’t just a normal cycle, but something far more durable,” says C. Fred Bergsten, the founding director of the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a former top U.S. Treasury official. “We’ve entered a period of steadily increasing dollar strength, with profound and negative effects on the U.S. economy and domestic policy, intensifying calls for protectionism.”

Whydoes a strong dollar mean lower sales for the Global 500? The reason is twofold. First, exports for U.S. corporations—the largest group on the list, with a total of 134 companies—weakened because the surging dollar meant that their prices were higher in foreign markets. Second, sales outside the U.S.—whether by U.S. or non-U.S. multi-nationals—in foreign currencies such as euros, yen, and yuan translated into far fewer dollars than they did last year. For instance, 1 billion euros in sales added up to $ 1.3 billion in 2014 and just $ 1.1 billion in 2015.

Part of this is technical, of course, driven by the fact that the Global 500 is calculated in dollars. To determine rankings, we use an average of exchange rates over the previous year to convert, say, Toshiba’s sales from yen into dollars. Incredibly, no fewer than 19 of the 21 currencies represented on the list retreated against the dollar in 2015. The euro fell 16.4% vs. the dollar, the yen slid 8.4%, and the yuan dipped 2%. Emerging-market currencies took the biggest hits—notably the Brazilian real (–29.4%) and the Russian ruble (–36.9%).

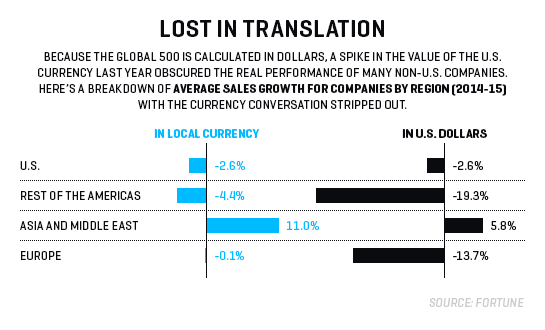

The best measure of how U.S. multi-nationals fared against foreign competitors is to strip out the conversion effect and compare revenue growth in home currencies. Overall, Asian companies performed the best last year, lifting their average sales in yen, rupees, and the like by 11%, vs. a 5.8% gain after conversion to dollars. China was an exception, however: Though the yuan fell slightly against the dollar, it appreciated strongly vs. most of the world’s currencies, pummeling exports of Chinese companies. European companies on average had flat sales in their local currencies. But many that did large volume in the U.S. performed brilliantly, as they got a boost from being able to produce their goods in euros or pounds and sell them in dollars.

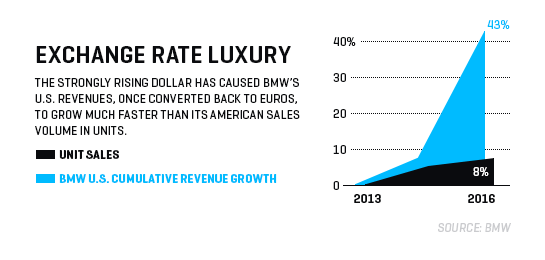

Consider BMW. Last year the luxury-auto maker grew its volume of vehicle sales in the U.S. by just 2.3%. But the dollar’s epic rise against the euro made the carmaker’s U.S. revenues worth far more when translated back into euros. As a result, its U.S. sales jumped to 18.2 billion euros, from 13.7 billion in 2014, a rise of 33%. Of BMW’s total sales increase of 11.8 billion euros, a full 38% was in the U.S., even though BMW sells only about 18% of its vehicles in America.

By contrast, U.S. multinationals generally lagged their global rivals. On average, U.S. companies suffered a 2.6% fall in revenues. The reason for the performance gap is, again, dollar driven: Large U.S. producers got a lot less from their sales outside the U.S. last year after converting back to dollars.

For one top name after another, the story is similar: Coca-Cola ko said its revenues would have risen 3% last year if the dollar had remained flat, but instead it suffered a 4% drop because of negative currency impact. Snack giant Mondelez mdlz saw its sales fall 13.5% and said that 12.6 percentage points of that decrease was due to exchange rates. And Walmart wmt , No. 1 on the Global 500 for the third straight year, said currency fluctuations against the strong dollar knocked $ 17.1 billion off its annual sales.

The strongly rising dollar has caused BMW’s U.S. revenues, once converted back to euros, to grow much faster than its American sales volume in units.

Looking forward, the dollar’s rise presents a pair of daunting challenges for U.S. companies. First, as long as the greenback keeps appreciating, it will continue to depress the U.S. economy’s rate of growth. That’s because a strong dollar hammers both exports and domestic sales of U.S. goods and services. When the dollar appreciates sharply, U.S. companies tend to protect their dollar margins by increasing prices in foreign currencies while at the same time rushing to lower costs. Companies exporting to the U.S., meanwhile, can lower prices in dollars and still garner far higher revenues than before. So U.S. companies lose market share at home too.

As a result, the U.S. trade deficit is poised to explode. “I expect that the deficit will expand from 3% to 5% of GDP,” says Robert Aliber, professor emeritus of international finance at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business. “That’s a lot of lost sales and lost jobs.”

In the view of most economists, the dollar is likely to keep appreciating for at least two more years, as investors are drawn to the relatively low-risk U.S. market. Bergsten of the Peterson Institute calculates that the hit from the trade gap lowered U.S. GDP growth in 2015 to 2.4%, from a potential 2.8%, and foresees a similar 0.4% drag for this year and 2017 too.

A second major challenge is that U.S. companies now face a large competitiveness gap. If global trade were growing rapidly, Asian and European consumers would still buy more of their favorite cars and computers even at higher prices. “In a low-growth environment, currency can make all the difference,” says Derek Scissors of the American Enterprise Institute. “Companies are battling for flat sales, and any increase in price can mean you sell a lot less volume.”

U.S. companies are likely to respond with layoffs and cost cutting, perhaps further heightening the protectionist movement that has already roiled the presidential election. “Historically, the biggest factor pushing a rise in protectionism and antiglobalization is a substantially overvalued dollar,” says Bergsten.

But Bergsten and other economists warn that a backlash against global trade—which could further suppress exports—is exactly what U.S. companies don’t need. The only real antidote? For the dollar to be a little less mighty, and as soon as possible.

A version of this article appears in the August 1, 2016 issue of Fortune with the headline “Beware the Almighty Dollar.”