The Fed Ignores Forewarnings of U.S. Labor Market Malaise

How many millions of people are unemployed in the United States?

This is a simple, yet deceptively complex, question.

For example, a person without a job who has completely stopped looking for employment is not, technically, in the labor market. Thus, they’re not officially unemployed.

Now let’s suppose someone has been laid off and only works a few hours a week part-time to make ends meet until they find another full-time job. That person isn’t considered to be unemployed, either.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), there are 7.4 million unemployed Americans. Dividing this figure by the size of the labor force produces a headline (U3) unemployment rate of 4.7%.

However, if marginally attached workers and those working part-time for economic reasons are included, the total (U6) unemployment rate is 9.7%.

The 5% gap between the U6 and U3 rates remains high relative to historical standards.

Keep in mind that even the U6 rate underestimates unemployment, though, because discouraged workers are excluded.

The Federal Reserve is aware (at least somewhat) of the limitations of these unemployment rates. And since full employment is half of the Fed’s dual mandate, it’s imperative that that our central bankers be able to gauge the true health of the labor market.

Index for Hire

In mid-2014, Fed staff members created the Labor Market Conditions Index (LMCI), which is derived from 19 labor market indicators.

The model for the LMCI incorporates measures of unemployment, underemployment, workweek length, wages, vacancies, layoffs, and quits, as well as labor market sentiment, derived from surveys of consumers and businesses.

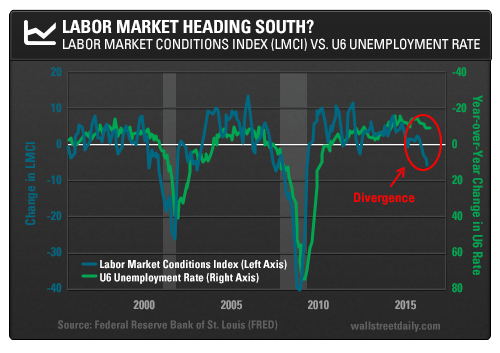

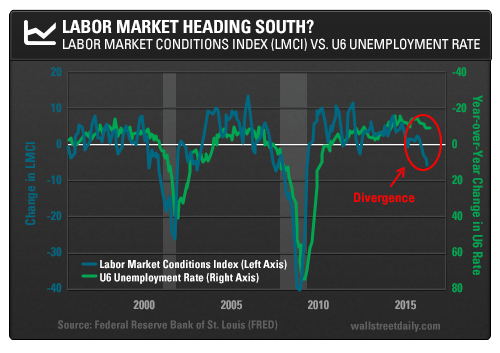

The change in the LMCI is charted below:

Also included is the inverse of the year-over-year change in the U6 rate on the right-hand axis.

It’s often said that employment data are lagging indicators, but the U6 rate did begin to rise (decline on the chart) just before the start of the last two recessions (shaded areas).

As you can see, the changes in the LMCI are far more volatile, but the index does seem to portend turns in the business cycle.

The LMCI declined to -6.2 in May 2000, 10 months before the ensuing recession began.

In August 2007, the LMCI hit -6.8. At the time, most economists were still blissfully unaware of the imminent Great Recession.

Interestingly, the LMCI also seems to presage recoveries.

Amidst the 2001 recession, the LMCI bottomed two months before the U6 peaked in rate of change terms. The LMCI also bottomed in December 2008, indicating that the Great Recession was almost over.

In total, the data suggest that the LMCI is a leading indicator and functions as a decent early warning signal for looming recessions.

Therefore, it’s concerning that the LMCI has now dropped to -4.8 – the lowest level in the past six years.

Unheeded Warnings

Curiously, Fed Chair Janet Yellen dismissed the LMCI at the press conference following last week’s Fed meeting.

When asked about the deterioration in the LMCI, Chair Yellen called the index an “experimental research product.” She then added: “As I look at it and as that index looks at things, the state of the labor market is still healthy, but there’s been something of a loss of momentum.”

According to the Fed’s proprietary labor market indicator, the labor market is softening. And yet, Chair Yellen downplays the development.

Many aren’t heeding the warning from the bond market, either.

At around 1.6%, the 10-year U.S. Treasury rate is plumbing 2012’s all-time low levels. And the spread between the 10-year and 2-year Treasury rate (2s10s spread) recently hit 0.88% – the narrowest spread in the post-crisis period.

With such low short-term policy rates, the 2s10s spread probably won’t invert as it did before past recessions.

Even so, the action in the Treasury market reflects slowing economic growth prospects, as well as incipient labor market malaise.

Given the LMCI and the bond market leading indicators, I believe the U3 and U6 unemployment rates have bottomed.

The stage is now set for a rise in unemployment. And if history is any indication, a recession will then soon follow.