Reasons to Doubt Chinese GDP Growth

The Communist Party of China, which is in power in the country, declared on Tuesday that they aim for growth of about 5% this year. Premier Li Qiang admitted that accomplishing that would be challenging. He continued by saying that despite “an array of interwoven difficulties” last year, the country’s growth rate was 5.2%, “ranking China among the fastest-growing major economies in the world.”

With falling population and property investment, how does China manage a 5% growth rate? I highly doubt that it does. The rate of actual growth is likely to be far slower.

Chinese GDP has long been treated with skepticism by Western analysts and even by many Chinese officials. However, doubts about the reliability of the data have increased in tandem with the number of contradictions, inconsistencies, and gaps in it.

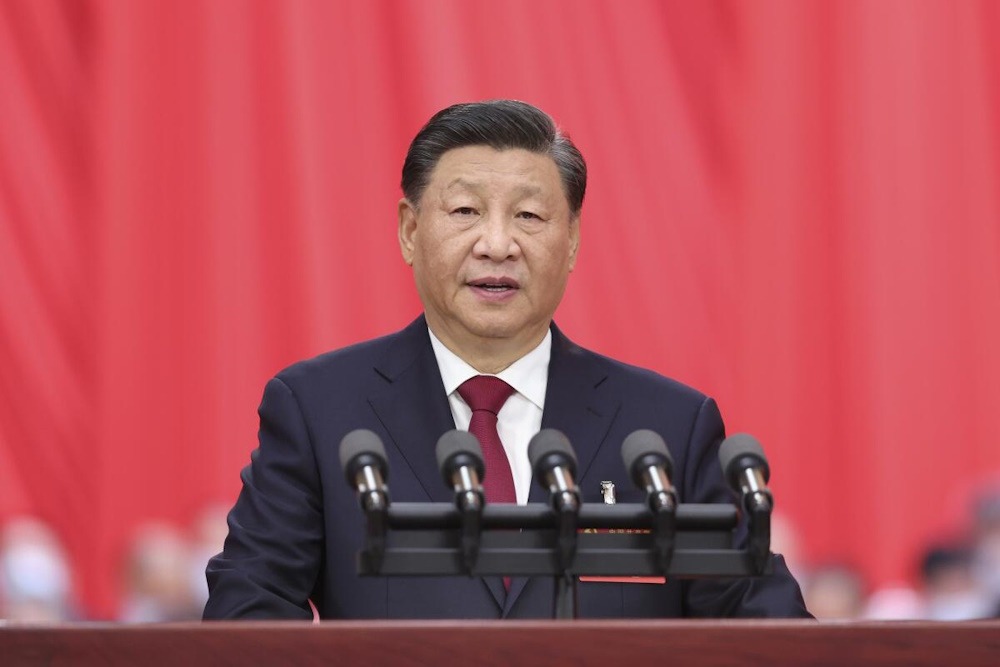

In the past, differences tended to support both the overstatement and the understatement of activity, but recently, they have tended to flatten growth. For President Xi Jinping, these actions further his larger objective of demonstrating to the world and his own people that China’s economic and political model is the best.

The data from China is significantly exaggerated, according to the New York-based Rhodium Group, which has researched the data for years. Rhodium predicts a decline in Chinese production in 2022, the year of the most extensive COVID-19 lockdowns, contrary to the 3% growth reported by official statistics. It lowers the official growth rate from 5.2% to 1.5% for last year. The newest goal was deemed “unrealistic,” particularly in the absence of substantial fiscal stimulus, although it anticipates growth increasing up this year.

While some analysts believe actual growth is higher than official statistics, others hold a less rosy view. The alternative projections projected growth in Finland at 1.3% in 2022 and 4.3% in 2018.

Data abnormalities are rampant, which fuels their distrust. The National Bureau of Statistics of China announced that retail sales for the last year increased by almost 7% when adjusted for inflation. Sales at retail establishments are just one part of a more comprehensive indicator of consumer and public sector spending.

According to Logan Wright, who heads up Rhodium’s research on China, separate NBS data suggests that real consumption increased by 11%. He said that this contradicts a mountain of other data, including declining online sales at Alibaba, increasing household deposits, and strain on local governments.

In order to make growth in the current year look stronger, China often adjusts down indicators from past years, but it doesn’t adjust down growth from earlier years. December saw a 0.5% downward revision to GDP levels by the NBS, which boosted growth in 2023 but maintained 2022 growth at 3%.

Based on a January article by Derek Scissors, chief economist at China Beige Book, the NBS is fond of modifications that improve present and future outcomes without altering previous ones.

One of China’s most widely monitored metrics, fixed-asset investment, is filled with such revisions. As of 2022 and 2023, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) estimated fixed-asset investment at 57 trillion yuan and 50 trillion yuan, respectively. The NBS, however, erred in its 2023 report, stating that investment climbed 3% rather than falling 12%.

Tell me how that’s possible. China Beige Book’s Shehzad Qazi speculated that, as it has done time and time again in recent years, the NBS may have quietly reduced the amount of investment for 2022.

Because, for instance, many projects may be sampled from year to year, the bureau states in a footnote that annual levels should not be used to compute growth. The data is made comparable over time by other statistical authorities.

Another oddity: the National Bureau of Statistics reports that investment in real estate fell 10% in 2023, but that investment in general, including building, was a major driver of economic development.

According to Rhodium’s Wright, if both claims are correct, then investment (not including real estate) must have increased at phenomenal rates. Still, earnings were feeling the heat, international investment was pulling out, and bank financing was becoming scarce. If there is an influx of private capital, where does it originate from? How does it pay for itself?

Historically, real GDP has been more stable than nominal GDP (i.e., before inflation adjustment) in China, indicating that inflation is artificially inflated to smooth growth. Approximately 7% nominal and 5% real growth were China’s projections for 2023 last year. Rather, real growth nevertheless reached 5.2%, while nominal growth was around 4%. These can only be made to fit if there was a 1% drop in prices instead of the expected 2% increase. Price increases and slower development were more probable, according to Wright, than what China asserts.

Physical indications, such as a 6.9% increase in power generation, a 5.7% increase in energy consumption, and an 8.1% increase in cargo transport, were used by a spokeswoman for the Chinese embassy in Washington to support last year’s growth numbers. The rebound in China is being propelled by consumers. Retail sales of services have increased by 20%, and the spokesman also mentioned that the rate of decrease in real estate has slowed.

There have been concerns regarding Chinese data for many years. For a while, the national GDP was lower than the sum of the provinces’ GDP reports. That is no longer a major concern.

Even so, the data quality in China is still lacking. A former head of the World Economic Outlook at the International Monetary Fund and current fellow at the Brookings Institution, Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, noted that GDP is released at a relatively rapid pace compared to other countries, but it is seldom revised and does not include fundamental data like quarterly spending by consumers, businesses, and the government. He stated that the statistical standards were inadequate.

Legislation in China forbids the fabrication or falsification of data and ensures the autonomy of staff statisticians. Nevertheless, China’s statistical bureau consistently hails the Communist Party “with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core,” in contrast to other bureaus that aim for political impartiality.

“No one views it as an attack on legitimacy of the government, the way it is in China,” Wright said, adding that disagreements about data quality occur in every country. The political climate becomes more volatile whenever anyone raises concerns about China’s economic development pace.

Due in part to the fact that data anomalies in China have always cut in both directions, not all analysts link them to politics. However, manipulating the data is becoming more and more vital if Beijing wants to bridge the gap between their politically required development and what is actually achievable.

“The growth target they set in the past many years have been too high to accomplish organically,” commented Riikka Nuutilainen, an economist at the Bank of Finland. “The authorities might be frightened to reduce the growth objective by the amount needed to achieve more balanced growth.”

As we’ve seen in previous years, this year’s goal “is quite ambitious” and might necessitate data smoothing.