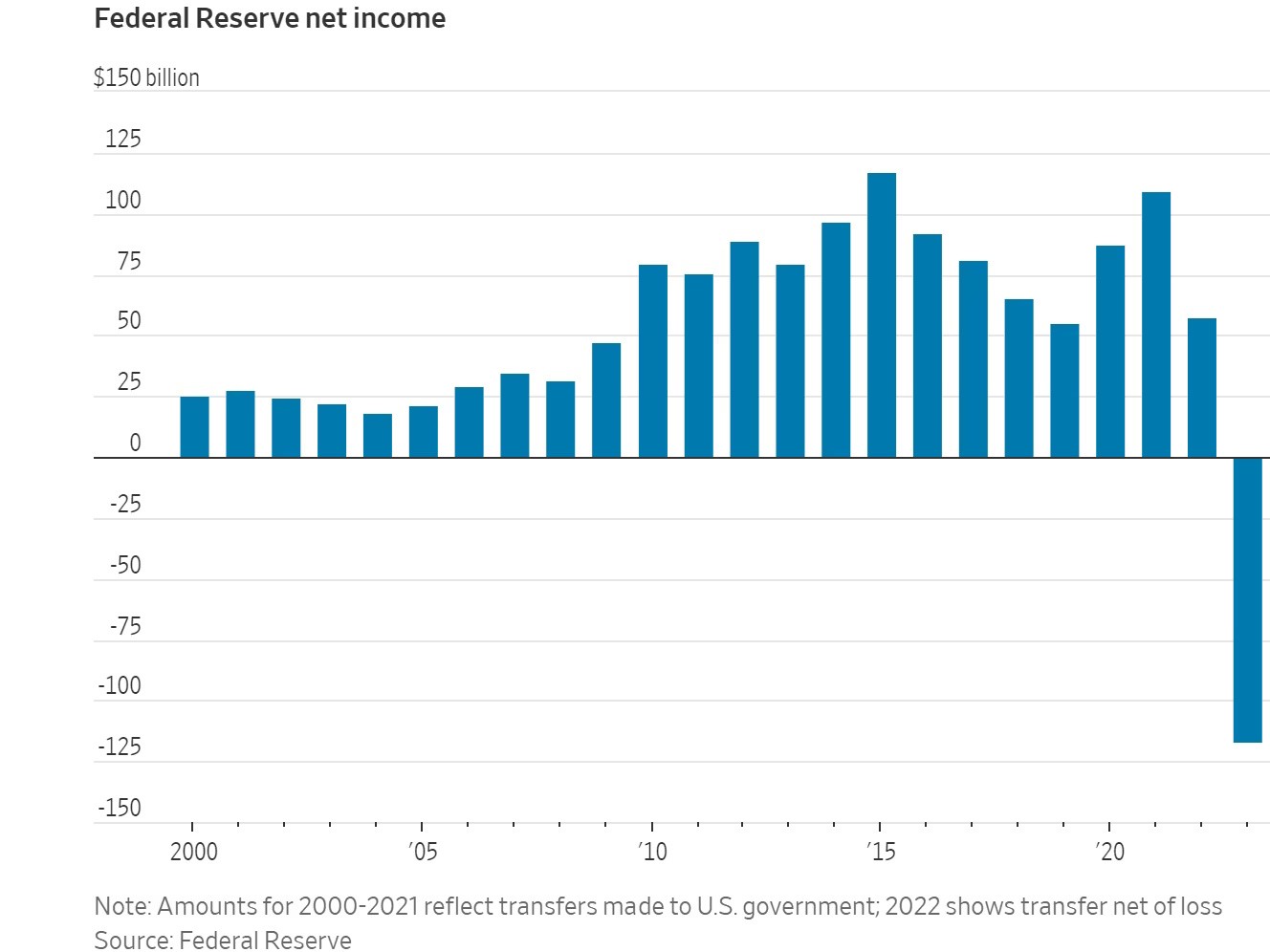

Fed Posts Largest-Ever Annual Operating Loss

The Federal Reserve ran an operating loss of $114.3 billion last year, its largest ever, a consequence of its campaign to aggressively support the economy in 2020 and 2021, then jacking up interest rates to combat high inflation.

The losses added to already large federal deficits that have required bigger auctions of Treasury debt. The central bank’s losses could continue for as long as short-term interest rates remain near current levels. That has the potential to fuel new political attacks on the Fed, though there have been no signs of that so far.

The U.S. central bank announced preliminary, unaudited results of its 2023 financial statements on Friday.

The central bank paid more to financial institutions on interest-bearing deposits and securities than it earned from securities that it bought when interest rates were lower. That’s a result of it raising its benchmark short-term interest rate to a two-decade high, above 5%, last year.

The losses don’t affect the Fed’s day-to-day operations and won’t require the central bank to ask for an infusion from the Treasury Department. Unlike federal agencies, the Fed doesn’t have to go to Congress hat in hand to cover operating losses. Instead, the Fed created an IOU in 2022 that it calls a “deferred asset.”

The Fed has almost always turned a profit and is required by law to send its earnings, minus operating expenses, to the Treasury. Those gains turned to losses in 2022, meaning the federal deficit has been a bit larger than it would otherwise have been.

During the first nine months of 2022, the Fed transferred $76 billion in earnings to the Treasury. In September of that year, it began running a loss, and it ended the year recording a $16.6 billion deferred asset. Until 2022, the Fed had never in its 109-year history suspended remittances to the Treasury for a meaningful period due to operating losses.

The Fed’s deferred asset grew by $116.4 billion last year, bringing its cumulative total to $133 billion. When the Fed is no longer running losses, it will pay itself back first and extinguish the deferred asset before resuming remittances to the Treasury.

When the Fed returns to profitability depends on when it lowers interest rates in the years ahead. The Fed sets rates at levels designed to keep inflation low and stable while boosting employment. It doesn’t focus on profits.

Fed losses are a side effect of its efforts to support the economy during the Covid-19 pandemic by purchasing large amounts of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities. The market value of those securities dropped after the central bank began raising rates aggressively in 2022 to combat inflation, but the Fed doesn’t book losses on them because they are held to maturity.

Instead, the Fed is running losses because it is paying more in interest than it earns on those securities. Beginning in September 2022, the overnight rates the Fed pays to banks on their deposits held at the Fed, called reserves, and on other securities transactions it conducts to manage interest rates, exceeded the income it collects on its $7.1 trillion in security holdings.

Those holdings consist primarily of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities that it accumulated during bond-buying stimulus programs between 2009 and 2014 and again between 2020 and 2022.

The Fed is likely to continue running accounting losses for as long as it holds interest rates above around 3.5% and shrinks its asset portfolio, a process that began in 2022. The Fed raised rates last year to a range between 5.25% and 5.5%.

Fed officials last decade expressed unease in private over the potential political blowback should it be forced to raise rates rapidly and incur losses on its securities holdings, according to transcripts of their policy meetings. While that is essentially what occurred over the last year and a half, elected officials in Washington have said little.

The central bank maintained a relatively small portfolio until the 2007-09 financial crisis, after which its holdings of Treasurys and mortgage bonds swelled and it revamped how it manages interest rates. Before that crisis, the Fed’s annual transfers to the Treasury ranged between $20 billion and $30 billion, or less than 1.5% of all federal receipts.

After that, the Fed’s net income soared as it held short-term rates at low levels while owning higher-yielding long-term securities. Between 2012 and 2021, remittances as a share of federal receipts nearly doubled. The Fed sent more than $870 billion to the Treasury over those 10 years, including $109 billion in 2021.