For Years, the World Was Eliminating Extreme Poverty. Here’s Why the Progress Is Stalling

Extreme poverty has been in a nose dive your whole life. But it may have hit an inflection point in 2014 and be in a slower decline now, according to the World Bank’s latest annual estimates.

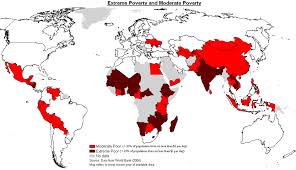

The World Bank, an international development agency based in Washington, D.C., uses an absolute rather than a relative measure to define it’s so-called International Poverty Line, which is now $ 1.90/day (in 2011 dollars). This year’s report, due out in full on Oct. 17, confirms projections that in 2015 some 10% of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty. The World Bank’s forecast for 2018 is 8.6% of the population.

While the rate was dropping by about one percentage point a year from 1990 to 2015, it appears to have stalled. Recent wars in Syria and Yemen have not helped, nor has fast population growth in many African countries that already suffered from poverty. Many development researchers attribute the lion’s share of the global reduction in poverty to China, which moved hundreds of millions of its people from rural suffering into upwardly-mobile urban lifestyles. Still, most of the rest of world has followed suit.

“Over the last 25 years, more than a billion people have lifted themselves out of extreme poverty, and the global poverty rate is now lower than it has ever been in recorded history,” World Bank president Jim Yong Kim said in a statement, “But if we are going to end poverty by 2030 we need much more investment, particularly in building human capital.”

Yesterday Bill and Melinda Gates released a report ahead of their Goalkeepers conference alluding to the same issues. The Gates report examines global progress toward the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which have a 2030 target date.

Some 400 million people, or 5% of the projected population, will still be living in extreme poverty by 2030, according to an Overseas Development Institute (ODI) report, also out this week. That would be a failure of one of the UN’s SDGs, which is to eradicate extreme poverty.

The ODI estimates that doing so would cost an additional $ 125 billion per year in health, education and social protection in the poorest countries. The richer countries can probably do it themselves via taxes and improving existing social services, the ODI estimates, but 48 countries will need outside help with financing and building infrastructure.

In addition to measuring global poverty and figuring out how to eradicate it, it’s worth watching which governments are doing something about global poverty. This week the Center for Global Development (CGD) released a ranking of 27 rich countries’ commitments to development: the U.S. ranks 23rd, behind Hungary. The CGD praises the U.S.’s commitment to keeping sea lanes open, but dinged it for its foreign aid, foreign direct investment policies, and its environmental record.

Luckily, global development doesn’t wait around for governments. Private investors and philanthropists can find their own way to the developing countries, which are ripe with investment opportunities in health and education, the Gates’ say.