Pressure and exhaustion cloud Xiaomi’s quick smartphone-to-EV transition

In the months leading up to the moment he collapsed in pain while grocery shopping with his young son, Wang Peizhi dedicated countless hours to meticulously preparing Xiaomi Corp.’s flagship store for the debut of its inaugural electric vehicle. Wang’s work accumulated following the announcement by the company, spearheaded by billionaire co-founder Lei Jun, of an ambitious strategy to become the first technology firm to successfully transition into automobile manufacturing. Lei, 55, placed his reputation on the line with the transition, a challenge that even Apple Inc. could not conquer, declaring it was his “last entrepreneurial project.” A crucial element in realizing that vision was Xiaomi’s retail network — a responsibility held by Wang. In a bid to rival industry giants such as BYD Co. and Tesla Inc. within China’s rapidly expanding EV market, the company has opted to revamp its retail strategy by transforming smartphone stores into showrooms that showcase full-sized sedans and SUVs. However, during the Covid pandemic, Xiaomi dismissed approximately half of the team involved in the initiative, retaining around 10 individuals, as reported by a former employee and a current staff member, both of whom collaborated with Wang and requested anonymity to address sensitive matters. The small team experienced a significant rise in their workload at the start of 2024, as the company hurried to establish EV stores ahead of the launch of its flagship SU7 sedan, according to sources. Wang dedicated increasingly longer hours to the team’s most significant projects, alongside his responsibilities for the routine maintenance of the company’s network of stores, they stated.

Additionally, he was stationed at Xiaomi’s headquarters in Beijing, which increased his visibility to the company’s top executives. During the initial eight months of the year, he was involved with a minimum of 267 retail stores, frequently updating them to include designated areas for electric vehicles, as revealed by a collection of internal documents, photographs, and WeChat messages examined. On Aug. 25, just under three days after collapsing in front of his son, he passed away from a heart attack at the age of 34. Local authorities determined that Wang’s death was not connected to his employment at Xiaomi. However, his widow firmly believes that his demanding work schedule played a role in his death. “He was treated just like a leaf: when it falls, people step on it without noticing its existence,” Luna Liu said. She consented to speak publicly for the first time since his death, believing that his case merits greater attention. She also shared thousands of her late husband’s work-related WeChat messages, expressing concern that Chinese companies exert excessive pressure on their employees, often neglecting their health and welfare.

Xiaomi entrusted Wang with greater responsibilities over the years due to his earnest approach to his duties. He oversaw several of the company’s most prominent projects, including its flagship showroom located just off Tiananmen Square. However, he still had numerous other projects to oversee concurrently. Wang’s motivation for working long hours is multifaceted. Individuals in his inner circle indicated that he experienced a profound sense of duty and often undertook responsibilities personally, as there was no one available to assist with his obligations. He also pushed himself relentlessly, meticulously monitoring hundreds of projects and working tirelessly to ensure he met the company’s demands. According to his widow, he was compensated generously by Chinese standards, earning approximately 600,000 yuan ($84,000) annually, which included stock options. However, she stated that he experienced “immense mental strain” as he navigated the pressures from senior company executives and the actual circumstances he faced. “He was sandwiched between his bosses and the stores whenever there was an issue with one of the projects,” she stated. In response to a detailed request for comment, a spokesperson for Xiaomi stated: “We are deeply saddened by the unfortunate passing of our colleague and extend our deepest condolences to his family and friends. At the same time, we do our utmost to provide support and assistance to our colleague’s family under the applicable laws and regulations.”

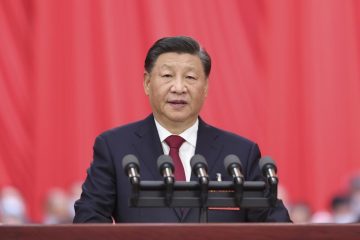

Xiaomi is not alone in encouraging its employees to put in extended hours. Employees throughout China’s technology industry express frustration over the extensive hours they dedicate to the office. Wang’s story provides an insightful look into the significant pressures faced within China’s tech companies. One reason is a renewed urgency to remain competitive in China’s increasingly crowded market, where the competition for customers in sectors ranging from EVs to e-commerce is fiercely intense. The competition with the US in the realms of semiconductors and AI has also influenced the culture within certain state-affiliated companies. Excessive work culture, referred to as “996” for the expectation to be in the office from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week, is firmly established in China’s tech sector. A decade ago, the prevailing sentiment was that hard work would yield rewards, as swift economic growth opened up opportunities, according to Mary Gallagher, professor of global affairs at the University of Notre Dame. However, the focus has shifted towards national priorities and a sense of patriotic duty as China engages in competition in chips, AI, and electric vehicles. “These industries that are doing so well — including on export markets — and are so important to the confidence that Xi Jinping wants to see in the economy,” said Gallagher, author of Authoritarian Legality in China: Law, Workers, and the State. “There’s enormous pressure in those places.”

Lei’s transition to electric vehicles commenced with a substantial investment of $1.4 billion, subsequently leading to extensive expenditures across nearly every aspect of the supply chain, including batteries, chips, air suspension, and sensors. Overall, it invested over $1.6 billion into more than 100 suppliers from 2021 to 2024, as reported by data. As EV production accelerated at the start of 2024, company leadership shifted their focus towards enhancing sales. Two months prior to the launch of the SU7 by Xiaomi, Wang assumed additional responsibilities. He was dispatching WeChat messages to colleagues from the early hours of the morning until late at night, with some originating from his residence. On a notably extended day at the close of January, he inquired about the installation of mirrors at an outlet around 2:30 a.m. A few hours later, he urged a furniture supplier to complete a project at a pace five times quicker than initially stated. “At one point, he was shouldering the workload of seven or eight people. He said he was busy like a spinning top,” remarked Wang’s widow, Liu. “Many times I told him, although you come back home every day, sometimes I feel I haven’t seen you for days.” Following the Lunar New Year holiday in February, Wang operated at an unyielding tempo, exchanging hundreds of photos and messages with colleagues regarding the flagship showroom in Beijing. As the location approached its completion at the end of March, Wang dedicated the entire night to laboring on the lighting system and charging poles in the basement. He also hurried to reinforce the floor after discovering it had cracked under the weight of a car.

On one evening, Xiaomi President Lu Weibing shared a post on Chinese social media, revealing that he would be making a long-anticipated visit to the flagship store in Beijing the following morning. Following the conversation with a colleague, Wang expressed concern over the tight timeline for preparing the showroom. “Tomorrow decides everything,” he wrote on WeChat. His hard work paid off: About two weeks later, Lei praised the flagship location as “one of the most iconic among our 59 stores nationwide.” The SU7 launch last March propelled Xiaomi into China’s EV market. With a price of 215,900 yuan, or approximately $30,000, it is positioned below the 219,800 yuan asking price for a BYD Han L and the 235,500 yuan cost of a Tesla Model 3. The Porsche Taycan, which the SU7 closely resembles, has a starting price of approximately $100,000. Since the unveiling, Xiaomi’s stock has surged approximately 200 percent in Hong Kong. However, the company still faces significant challenges before it can join the ranks of the elite automakers. It has established a delivery target of 350,000 units in 2025, an increase from its earlier goal of 300,000. In contrast, BYD Co., China’s leading car manufacturer, achieved sales of approximately 4.3 million electric vehicles and hybrids last year, with a significant portion sold internationally, whereas Tesla reported global sales of around 1.8 million vehicles. Xiaomi has successfully “democratise technology” and established a brand image that strongly appeals to Chinese consumers, stated Bill Russo. “Xiaomi is a known consumer brand that makes technology affordable, and that’s been their value prop from the beginning for virtually every device that they manufacture,” said Russo. “Lei Jun is viewed as a rock star by the Chinese consumer.”

In recent years, China has been engaged in a national discussion regarding the necessity of enhancing work-life balance. Social media platforms such as Weibo and Xiaohongshu have seen an influx of posts — which remain unverifiable — regarding extended working hours. The issue has gained significant attention in recent years due to a number of high-profile deaths linked to overwork, prompting the ruling Chinese Communist Party to express its support for safeguarding workers’ rights. During the pandemic, there seemed to be an improvement in work culture, particularly as some tech staff were granted the opportunity to work flexible hours. The government has initiated efforts to enhance working environments in response to the public outcry that followed a series of deaths linked to overwork. Public officials engaged in discussions and unveiled plans to enhance working conditions. In 2021, Chinese authorities initiated an investigation into the working conditions at the e-commerce company PDD Holdings Inc. after the tragic death of an employee in her early 20s. An employee collapsed while walking home with colleagues. Her death ignited a wave of criticism on social media directed at PDD and the unyielding work schedules imposed on its employees. The subsequent year, a content moderator at Bilibili Inc., the largest anime streaming platform in China, passed away due to a brain hemorrhage. Both companies have asserted their innocence. Requests for comment went unanswered by both PDD and Bilibili.

China’s national labour laws set a maximum standard working time of 44 hours per week. Employers have the opportunity to engage in negotiations with trade unions and employees to extend that. Data from the National Bureau of Statistics indicate that employees at Chinese companies have been logging longer hours in recent years. Last year, the average workweek reached 49 hours without any breaks, a slight increase from 47.9 hours in 2022. According to a survey, American full-time employees worked an average of 43 hours a week last year. This year, the government unveiled an action plan to “regulate the unwholesome work culture,” urging provincial governments to assume a more significant role in curbing excessive hours. “Local authorities are urged to better protect workers’ rights to rest and tighten supervision over employers’ behaviors of illegally lengthening employees’ working hours without permission,” reported the state-owned outlet China Daily in March. However, the issue remains unresolved. Engineers at Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. canceled their vacations and worked through this year’s Lunar New Year holiday to catch up after DeepSeek stunned the global tech industry with its low-cost, powerful AI model in January. PDD, engaged in a fierce price competition with Alibaba and JD.com, also required some employees to forgo their holiday plans during this time. However, it provided overtime bonuses to employees who remained to maintain the functionality of their website, stated one anonymous employee in Shanghai regarding their work schedule. The employee, in her mid-30s, stated, “I received a bonus of roughly 3,000 yuan after working four days during the holidays.” Requests for comment from Alibaba and PDD went unanswered. Another engineer at Ueascend, a chip equipment maker based in Shanghai, stated that he has only been able to take one day off per week since joining the company last year. Team calls occasionally took place on the limited days he had off, and when pressing projects arose, he would work from morning until 11 p.m. “for days,” said the 25-year-old, who also asked for anonymity to discuss their working hours. Employees at drone manufacturer DJI and Apple supplier Desay Battery have also reported inadequate working conditions. Desay Battery declined to provide a comment when approached for a response. A spokesperson for DJI stated that their employees typically work nine hours each day and often enjoy a two-day weekend.

In April, reports indicated that Xiaomi was mandating employees to work a minimum of 11.5 hours each day, with those logging less than eight hours required to provide a formal explanation. Xiaomi has not provided a response to inquiries regarding the media reports. A survey released last year revealed that Xiaomi employees worked an average of 11.5 hours per day, ranking among the longest hours in the country’s tech sector. According to the survey, staff at ByteDance Ltd., Meituan, and Tencent Holdings Ltd. all recorded double-digit hours, although the methodology was not explained. In the United States, the typical workday lasted 8 hours and 44 minutes, with only 5 percent of employees engaged in work during the weekends. ByteDance chose not to provide a comment, and Meituan and Tencent did not reply to inquiries. Wang’s long hours were certainly recognized. His internal performance review, which encompassed the first half of 2024, noted that he received commendations from his superiors for his efforts in expanding Xiaomi’s network of EV showrooms. The company acknowledged his efforts in launching new stores “at a unified standard, with high efficiency and quality,” according to the review.

In the weeks preceding his death in August 2024, Wang was engaged with at least 80 stores, as indicated by his WeChat messages. While the majority of the locations he explored were in Beijing, he maintained a hectic itinerary, traversing the expanse of northeastern China. According to one of the former colleagues, only two team members were available to assist him with a wide array of tasks, which encompassed renovation, supplier management, and accounting. Over the course of three days at the start of the month, he made visits to no fewer than 14 Xiaomi outlets located in Harbin, Changchun, and Shenyang. His final business trip occurred on August 20, during which he visited at least three stores in Tianjin, located approximately 30 minutes from Beijing by train or a 1.5-hour drive. On August 22, Wang experienced such weakness that he decided to call in sick and sought medical attention at the hospital for evaluations. During his time there, he received numerous WeChat messages from employees at approximately five different outlets. He informed a store manager in Shenyang that he was unwell and that another individual would be visiting his projects that day. “Xiaomi’s employees are all warriors,” the manager replied, encouraging Wang to improve and adding a crying facepalm emoji. The work exchanges continued until at least 4 p.m. Later that day, he accompanied his son on a trip to the grocery store. In that moment, his heart seized up, momentarily halting the flow of blood to his brain, and he collapsed to the floor. According to his widow, he was rushed to an intensive care unit by ambulance. Fewer than three days later, he was dead.

According to his widow, Wang was in good health at the time of his death, had no pre-existing conditions, and maintained an active lifestyle. She said he underwent regular annual physical exams but missed his appointment in 2024 due to a scheduling conflict. He dedicated his time off to his family, enjoying hikes in the mountains surrounding Beijing and attending extracurricular activities with his son, as she and a colleague noted. “He regularly went on 5-kilometer runs to ease the stress of his job,” another colleague said. Wang’s widow informed Xiaomi that she believed her husband had succumbed to the pressures of excessive work. The company informed local authorities about the incident, which concluded that Wang’s death was not related to work. Chinese guidelines stipulate that an employee is considered to have experienced a work-related death only if they pass away within 48 hours of receiving treatment for an injury incurred while on the job. The Beijing Municipal Human Resources and Social Security Bureau has not provided a response to the request for comment. Xiaomi has refuted any allegations of misconduct. It subsequently proposed a hardship payment of 50,000 yuan, approximately $7,000, to the family; however, she stated that no funds were disbursed. The company assisted her in accessing her husband’s investment portfolio; however, she noted that they later rescinded some of his stock options. Just days following her husband’s death, Liu reached out to Xiaomi’s CEO. “I hope Mr. Lei can take a look at employee Wang Peizhi’s sudden death,” she wrote. “My husband contributed to the success of Xiaomi’s EVs.” He was exhausted due to the overwhelming pressure from work. Her posts garnered minimal attention, with certain users remarking that she was merely pursuing extra compensation from Xiaomi. By the end of the year, she ceased her activity on Weibo. “It’s okay if I was misunderstood or insulted, but the company still owes me an apology,” she stated in one of her final posts.

According to two of his former colleagues, Wang’s death was not widely reported within Xiaomi. Zhang Jian, an executive at Xiaomi responsible for nationwide stores during that period, led an internal meeting regarding Wang’s death, as reported by a current employee. He informed colleagues that Wang had passed away due to a heart attack and that the company was in communication with his family. The team’s working hours remained unchanged. (Ultimately, Zhang ascended to lead the company’s electric vehicle sales in China.) The current workload at the company fluctuates across different departments. A current employee noted, “On Wang’s former team, tasks usually pile up at the end of the month.” A current Xiaomi employee from a different team in Beijing stated, “They usually work between 50 and 60 hours per week and rarely go in on weekends.” A different member of the company’s smartphone research team reported that they often exceed 50 hours of work each week, which sometimes includes hours on Saturday and Sunday. Wang’s widow stated that he left his family with debts amounting to approximately 4 million yuan, which includes the mortgage on their home. His life insurance policy, provided by Xiaomi, disbursed a one-time payment of approximately 800,000 yuan. In her residence in Beijing, she has endeavored to reconstruct the memories of her deceased husband by meticulously organizing his WeChat chat logs — the majority of which pertain to his professional life. However, she lacks access to a distinct application he utilized for internal Xiaomi communications, resulting in an incomplete understanding of his job responsibilities. What she is certain of is that she did not see her husband frequently during his final months.

Eric Whitman

Eric Whitman is our Senior Correspondent who has been reporting on Stock Market for last 5+ years. He handles news for UK and Europe. He is based in London