Chinese Video Game ‘Kill Line’ Shows US Poverty and Claims Superiority

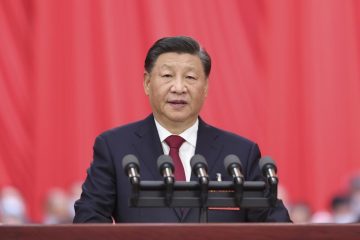

Chinese commentators are currently engaging in extensive discussions regarding poverty in the United States, asserting China’s superiority by adopting a striking phrase from video game culture. The term “kill line” refers to the moment in gaming when the health of opposing players has declined to such an extent that they can be eliminated with a single shot. It has now evolved into a consistent symbol within Communist Party propaganda. “Kill line” has been utilized consistently across social media, commentary platforms, and news outlets associated with the state. It has gained traction in China to illustrate the horror of American poverty — a fatal threshold beyond which recovery to a better life becomes impossible. The phrase serves as a metaphor that captures the complexities of homelessness, debt, addiction, and economic insecurity. In its official use, the “kill line” looms over the heads of Americans, yet it is a concern that Chinese people do not have to face. The portrayal of the United States as a nation grappling with profound and pervasive economic difficulties has long been a staple of official Chinese communications. However, the phrasing and imagery associated with the “kill line” is a recent development. The essence lies in the straightforwardness of what it conveys: a sudden boundary where suffering commences and a joyful existence is irrevocably forfeited. The narrative aims to provide emotional relief to the people of China while seeking to divert criticism directed at its leaders. The more dire the situation appears across the Pacific, the reasoning behind the propaganda suggests, the more acceptable current challenges seem to be.

It is no coincidence that there is a surge of these messages at this time. China’s economic growth has diminished to half of its previous levels. Youth unemployment remains at elevated levels. Familiar routes to security — stable employment, increasing property values, consistent upward mobility — have grown more uncertain. For numerous families, the margin for error appears to be more precarious than it used to be. In an essay published online in late December, legal blogger Li Yuchen contended that the allure of the “kill line” concept lay in its convenience. He wrote that it allowed Chinese people to condemn a distant system while avoiding uncomfortable questions about their own lives. “Functions less as an analytical tool than an emotional interpreter,” he wrote. His essay faced removal by censors, becoming part of an extensive catalog of content eliminated for challenging official economic narratives. Societal inequality is indeed a significant issue in both China and the United States. The American economy undoubtedly places numerous individuals in precarious situations. The causes are multifaceted. However, in China, the experience and perception of poverty differ significantly.

In many Chinese cities, street begging and visible homelessness are closely regulated, resulting in their diminished presence in everyday life. Numerous urban dwellers experience these scenarios solely via international coverage, which is then rehashed by Chinese state media, focusing on the United States and other regions. Economic insecurity continues to be prevalent in China. Approximately 600 million individuals, representing around 40 percent of the population, earn roughly $1,700 annually. Rural pensions frequently total merely $20 or $30 each month, and a significant illness can plunge families into a financial crisis. The apprehension of depleting financial resources is a significant factor contributing to China’s status as having one of the highest household savings rates globally. However, these pressures are depicted as integral to a culture of resilience and accountability, equipping families to navigate unforeseen life challenges. For older Chinese, the use of American poverty for domestic political purposes is a well-known phenomenon. During the Cultural Revolution, a notable slogan declared that “happy Chinese people deeply cared about the American people living in misery,” despite the fact that the majority of Chinese citizens were experiencing poverty themselves.

During my childhood in China in the early 1980s, my family had a subscription to China Children’s News, which featured a weekly column with a straightforward slogan: “Socialism is good; capitalism is bad.” It depicted elderly individuals in American cities foraging for sustenance, and homeless individuals succumbing to the cold. The narratives were not fabricated; however, they were devoid of context and portrayed as the prevailing experiences within American society. A significant portion of Chinese society remained isolated from the global community, resulting in a scarcity of trustworthy information. It was hardly surprising that a significant number of individuals embraced such narratives. It is noteworthy that comparable representations still hold significance today, even with the increased access to information, despite the presence of state control. The approach is straightforward: amplify the plight of others to divert attention from issues at home. That approach is currently being defined through the metaphor of the “kill line.” The phrase is thought to have gained prominence in this new context on the Bilibili video platform in early November, attributed to a user identified as Squid King.

In a five-hour video, he compiled what he asserted were firsthand experiences of poverty from his time spent in the United States. His video featured poignant scenes of children knocking on doors on a cold Halloween night in search of food, delivery workers enduring hunger due to their meager wages, and injured laborers being discharged from hospitals for their inability to pay. The scenes were depicted not as isolated incidents but as proof of a larger system: Above the “kill line,” life persists; below it, society ceases to regard individuals as human. The story extended beyond the Squid King video, with numerous individuals online echoing his anecdotes. Essays on the nationalist news site Guancha and China’s largest social media platform, WeChat, characterized the “kill line” as the “real operating logic” of American capitalism. Others referenced instances of Western journalism that they believed highlighted the contrasts between America and China. By late December, the “kill line” framework had garnered official momentum, appearing in state media, theoretical journals, and propaganda commentary, while some voices cautiously turned the phrase inward, noting that confronting reality is often harder than repeating a metaphor.