One of Donald Trump’s most effective slogans during the presidential campaign was “America First.”

Evidence from exit polls shows that in formerly Democrat-leaning states that were decisive in Donald Trump’s victory—including Michigan and Wisconsin—Trump voters were most concerned about the economy, trade, and what trade policy has done to blue-collar jobs.

This is not surprising, given the fact that the key point of departure between Donald Trump and traditional Republicanism was the hard line he took against free-trade agreements and the skepticism with which he viewed globalization and the changing demographics of America.

But how Trump will satisfy voters who supported him on the promise that he could reverse the effects of globalization is not altogether clear. According to a new report by Pankaj Ghemawat, an economist at the Stern School of Business at New York University, actual trends in globalization are much different than the political rhetoric from the 2016 election would suggest.

For one, growth in cross-border trade has slowed dramatically over the past several years. Meanwhile, the U.S. actually ranks pretty far down the list of countries in terms of depth of global trade integration, meaning that much less of the economic growth in America is due to international trade than a typical wealthy country.

This means that when it comes to fighting the sort of globalization that has American voters anxious, Trump’s emphasis on free trade is an example of fighting the last war. Evidence shows that free trade deals, relatively speaking, haven’t eliminated a large number of jobs when compared with other factors like technological change. Nor is there any reason to believe that instituting tariffs would convince companies that have already shipped production overseas to bring back those jobs.

The WTO predicts that next year, trade growth will only be 80% as large as GDP growth, a much lower ratio than we’ve seen in recent years. That suggests that increases in economic activity around the world will be much more reliant on activity within national borders rather than across them. But that doesn’t mean that the voter frustration that Donald Trump leveraged is not based in fact. “When one looks at pretty much any other dimension of globalization including capital flows, people flows and information flows, things are generally up.” Ghemawat says. “I find this useful because though there has been a lot of talk of ‘the end of globalization,’ it seems to be entirely based on the trade numbers without paying attention to these other measures.”

And there is clear evidence that these other measures of globalization, including immigration to America, the flow of information into the country from globalist forces outside the U.S., and the flow of capital in the form of foreigners buying U.S. assets continues to grow healthily. Let’s take these issues one at a time:

Capital Flows

There is a tendency on the right to fear-monger about Chinese or other foreigners buying up U.S. real estate, companies and other assets. Donald Trump has been making hay on this issue since the 1980s, when he complained about the Japanese buying up Manhattan real estate. But foreign direct investment supports U.S. jobs, lowers trade deficits, and announces foreigners’ confidence in the strength of the the U.S. economy.

Outside of protecting against foreign ownership of industries that are key to national security, it doesn’t make a lot of sense to fight this type of globalization. In fact, fighting it could very well hurt more workers than it helps.

Information Flows

There has been no better evidence of the ease of information flows than the 2016 election. There’s evidence that the Russian government was involved with hacks into Hillary Clinton’s campaign, while a foreign media organization, Wikileaks, put a lot of effort into embarrassing Clinton. Meanwhile, foreign news organizations like the Guardian campaigned hard against Trump and found receptive audiences in the U.S.

While some Americans might not like this trend, it’s difficult to see why a society that values free speech and the pursuit of knowledge would want or be willing to take the steps to stop this form of globalization.

Immigration

This is an area where the U.S. government can take real measures to blunt the effects of globalization on its citizens. While Donald Trump campaign has received a great deal of attention for his promise to deport illegal immigrants, what has received less attention was his pledge to reduce legal immigration, which he laid out during a speech in Arizona in August. As Trump said at the time:

We’ve admitted 59 million immigrants to the United States between 1965 and 2015.

Many of these arrivals have greatly enriched our country. But we now have an obligation to them, and to their children, to control future immigration – as we have following previous immigration waves – to ensure assimilation, integration and upward mobility.

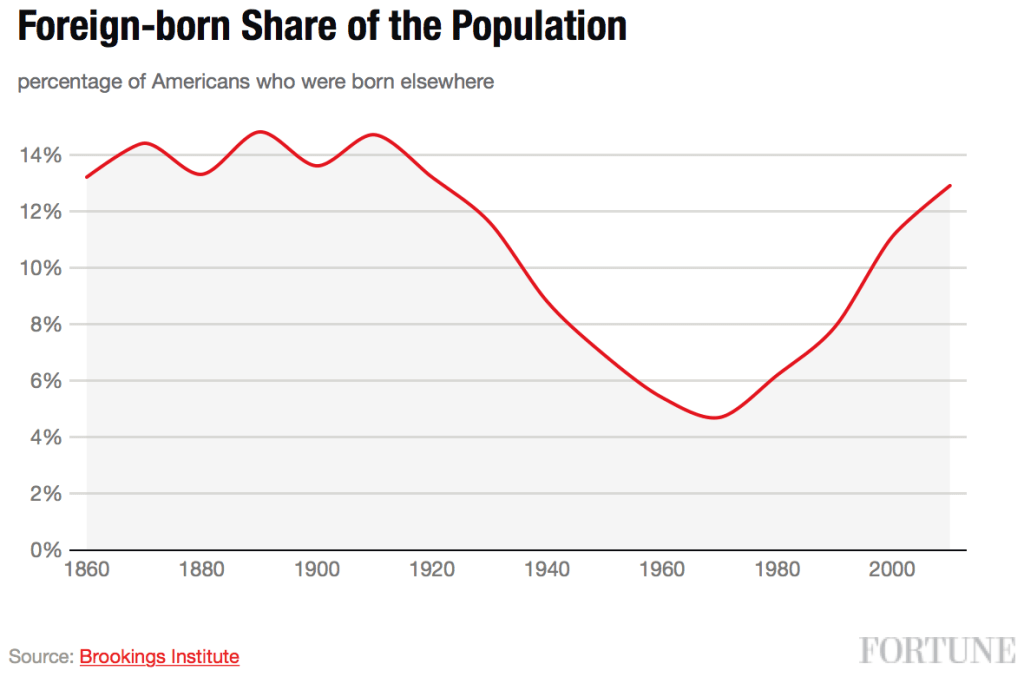

Within just a few years immigration as a share of national population is set to break all historical records.

Trump’s point is vividly reflected by the abovechart:

With the U.S. allowing in roughly 1 million immigrants per year, and with the birthrate of native Americans at all-time lows, we are indeed on pace to reach all-time highs in the share of Americans born outside the country.

Standard economic theory says that immigration is good for an economy—because it creates more demand for goods and helps grow the labor force. Still, immigration has its drawbacks both economically and socially. The U.S.—unlike, say, Canada—allows in a high proportion of low-skilled workers, which puts downward pressure on the wages of working-class Americans who are already being hurt by broader forces in the global economy.

And the 2016 election has shown that many Americans are simply uncomfortable with the changing demographics of their country, a feeling that in a democracy must at the very least be reckoned with, if not respected. That’s why it may make sense for Democrats and Republicans to come together to limit legal immigration, despite the economic drawbacks, in an effort to show those constituents that their concerns are being heard. In return, social progressives may convince immigration hardliners to take a more humanitarian approach to undocumented immigrants already here.

Globalization is in many ways a force beyond our control. But that doesn’t mean the government shouldn’t act to soften edges of the process, which in coming years will increasingly take the form of greater migration.