What the New All-Time High for the S&P 500 Says About the Economy

The stock market is flying high again.

American stocks once again reached all-time highs with the value of the S&P 500 looking like it would close on Monday at a new record. The stock market index was trading at 2,140 by mid-afternoon. The only other time the S&P 500 closed above 2130 was in mid-May of 2015.

Oddly, that doesn’t seem to be lifting anyone spirits. According to polling from gallup, most Americans will tell you that the U.S. economy is getting worse, not better. And this negativity has been with us ever since the financial crisis.

When the S&P 500 finally reached a new high in 2013 after years of clawing back the value lost during the financial crisis, the financial press used it as an opportunity to discuss a supposed disconnect between financial markets and the real economy. “Dow record? Who cares? Economy still stinks!” read one succinct headline.

Since that time, however, most economic indicators that describe the economic experience of the average American have improved. The unemployment rate has fallen to an historically low 4.9%, wage growth has accelerated, and home values have continued to rise.

![]()

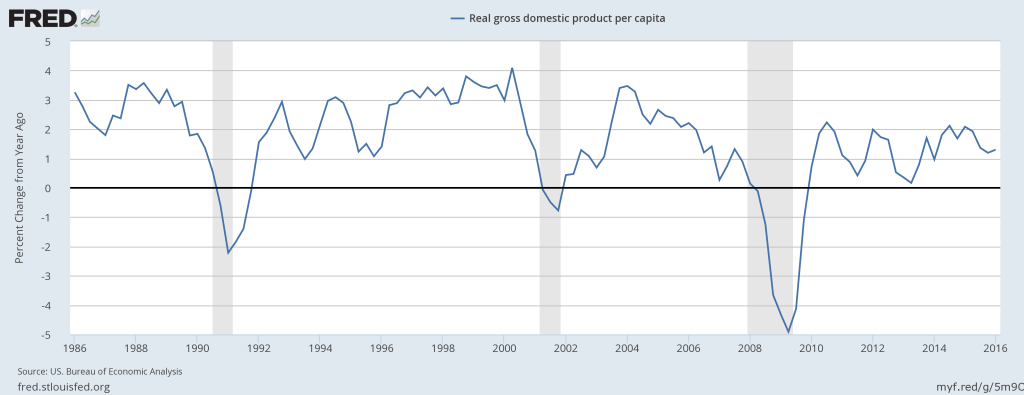

This shouldn’t come as a surprise. Despite the successful efforts of those with political axes to grind to distract from this fact, the fortunes of Wall Street and Main Street are closely intertwined. There simply is no way for investors to justify ever higher valuations for the companies on the S&P 500 without steady and significant economic growth that makes higher profits down the road possible. And if you take a look at the economic growth we have seen since the end of the financial crisis, that investor optimism appears justified.

Over the past thirty years, economic growth per capita has averaged 1.6% per year. In the first quarter of 2016, year-over-year annualized per capita growth was 1.3%. So while there is some truth to the idea that the economy isn’t performing as well today as it has in the past, this idea has been over exaggerated by those trying to score political points or those employing hyperbole in order to get attention.

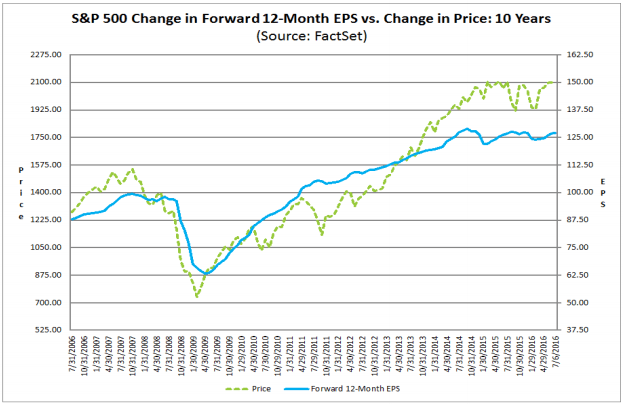

At the same time, there’s also evidence to suggest that investors are putting more money into stocks today than they would have at other points in American history. The price-to-earnings ratio of the S&P 500, for instance, has been trending higher for years now. That means that it takes less in profits today to justify a higher stock price than it did in years past. One reason for this is that central banks around the world have been buying up safe government debt in an effort to increase economic growth and inflation, leaving fewer of these assets for private investors to buy.

The above chart captures this dynamic, as it shows the price of stocks on the S&P 500 rising faster than actual estimates of earnings by those companies. This is one of the data points folks who argue that the stock market is becoming unmoored from economic fundamentals point to.

What’s more, investors are shrugging off the fact that corporate profits have been flat for roughly a year. The reason: Corporate profit margins hit all time highs after the recession as employers had leveraged a weak economy to push down wages. The fact that profits are falling at the same time that wage growth is accelerating is likely being taken as a sign by investors that the economy is rebalancing itself, with workers set to take a bigger share of the economic pie in quarters, rather than evidence of an economy about to slow.

And in the long run, this would be great for the U.S. economy, given the fact that the biggest difference between the economy today and that of a generation or two ago is growing income and wealth inequality. Economists across the political spectrum see this dynamic as a potentially serious threat to future economic growth, and one that could be holding back consumer spending and higher corporate profits today.

UCLA economist Roger Farmer has described the relationship between the stock market and economy as “like two drunks walking down the street, tied together by a rope. The drunks can wander apart from each other in the short run, but in the long run they can never get too far apart.”

And while the stock market may be still be a bit ahead of its drinking buddy, the economy seems less far behind the last time we crossed into new high territory.