Tariffs can be lifted, but a recession may be inevitable.

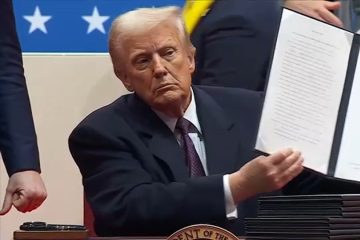

The U.S. economy appears to be on the brink of a potential recession, influenced by contractionary measures such as a reduction in the federal government’s scale, the implementation of broad tariffs, and increased deportations. The implementation of these policies poses a significant threat to employment levels, the viability of businesses, and the trajectory of wage growth. The scenario is exacerbated by a shifting labor market and a rise in income disparity. The US economy appears to be gradually heading toward a recession, driven by the Trump administration’s implementation of three contractionary policies simultaneously: downsizing the federal government, imposing widespread tariffs, and deporting workers. Should the policies that contract economic activity remain in place, a recession appears inevitable.

Economic downturns are a natural occurrence in the business cycle. Since the conclusion of World War II, we have experienced 13 instances of suffering. They all resonate with established patterns. Employment opportunities will diminish, recruitment activities will decelerate, and the unemployment rate is expected to increase. Furthermore, enterprises will close their doors, employees will withdraw from the labor market, and wage growth will remain sluggish. Once a recovery commences, it may require several years for the economy to achieve full restoration. Nevertheless, every recession possesses distinct characteristics. The perpetual transformation of economic landscapes ensures that the circumstances associated with recessions and recoveries are invariably distinct. Considering this, it is prudent to assess the factors that will distinguish the forthcoming economic downturn.

Initially, it can be contended that this recession is uniquely attributable to the policies enacted by the White House. Indeed, while it is true that most contractions incorporate a policy dimension, there exist numerous opportunities for recalibration between the initial cause and its subsequent effects. The 2008 recession, which coincided with the global financial crisis and extended into 2009, was partially triggered by the decision made during the Clinton administration to refrain from regulating over-the-counter derivatives, despite prior warnings regarding the risks associated with their lack of transparency. One potential silver lining is that, despite the closure of federal agencies, the majority of employees affected are technically on leave, allowing them to continue receiving their full salaries. The Department of Government Efficiency has asserted significant savings; however, these claims do not withstand rigorous examination, and there is a lack of evidence indicating a reduction in spending. The deportation efforts have concentrated on limited cohorts of individuals, significantly lacking the large-scale expulsions that were pledged by the White House.

Tariffs, both those imposed by the administration and the retaliatory measures enacted by trading partners, are stifling business activity and unsettling consumer confidence. Wall Street firms are swiftly revising downward their projections for the growth of gross domestic product. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s closely monitored index reflecting the current state of the economy has registered a negative value. Recent data from the Conference Board and the University of Michigan indicate significant downturns in consumer confidence levels. The impending recession raises two questions that were not relevant in previous economic downturns. Initially, one must consider whether legislators will retract a policy that is contributing to a recession as economic activity declines. Furthermore, should they take such actions, will it suffice to avert or mitigate the impending recession? Neither question yields a definitive answer; only conjectures persist. President Donald Trump has begun to acknowledge the likelihood of an impending recession, suggesting that economic hardship is a requisite step toward realizing his concept of a “Golden Age” for America.

The situation may have already reached a point of no return. Recessions frequently exhibit self-fulfilling characteristics; when a significant number of individuals anticipate an economic downturn, their behaviors—such as reduced consumer spending and preemptive workforce reductions by businesses—can precipitate the very decline they fear. During recessions, aggregate demand is adversely affected by three primary factors: the unemployment of workers, the anxiety of those fearing job loss, and the stagnation of wage growth for those who remain employed. All three cohorts exhibit a reduction in expenditure to differing extents. While tariffs may be adjustable, the question remains whether demand can be revitalized.

This recession, irrespective of its underlying cause, will challenge the economy through the introduction of two novel variables. The initial observation is that the substantial Baby Boomer cohort, with the youngest members now at 61 years of age, has largely transitioned into retirement. The alteration in the age distribution of the labor market indicates a significant shift towards a younger demographic. Research indicates that the effectiveness of monetary policy is influenced by age demographics. A younger demographic (under 35) mitigates it, whereas a middle-aged demographic (40-65) intensifies it. Income and wealth inequality has reached unprecedented levels. The highest-earning 10% of households receive nearly 50% of total income and represent slightly more than 50% of overall expenditure. The occurrence of a recession impacting an economy heavily reliant on a singular sector presents a novel challenge. This cohort has demonstrated a heightened responsiveness to variations in the stock market regarding their expenditure patterns. The actions taken during the forthcoming downturn could exert a disproportionate influence on the economy relative to previous recessions. In any economic system, numerous individuals engage in spending out of necessity, particularly to acquire essential goods such as groceries. What occurs to aggregate demand when it becomes increasingly dependent on individuals who are motivated to spend due to the perception of increased asset values?

Every post-war recession has its own grim distinction: the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression (2020), the most consecutive months of job losses (2008-2009), the longest duration to recover lost jobs (2008-2009), the briefest interval since the previous recession (1981), the most severe supply shock (1973), among others. This instance’s notoriety stems from its unique characteristic of being self-inflicted. Those with a keen interest in monetary policy history might argue that the recession of 1981 was largely a consequence of a deliberately stringent interest rate strategy. However, this approach was a reaction to severe economic circumstances, notably inflation rates exceeding 10%. Tariffs, reductions in government expenditure, and deportations are measures being implemented in response to an unemployment rate of 4% and inflation rates remaining below 3%. One represents an unavoidable burden, while the other is a choice made willingly. That is a particularly egregious form of honorific, if one were to consider the implications.