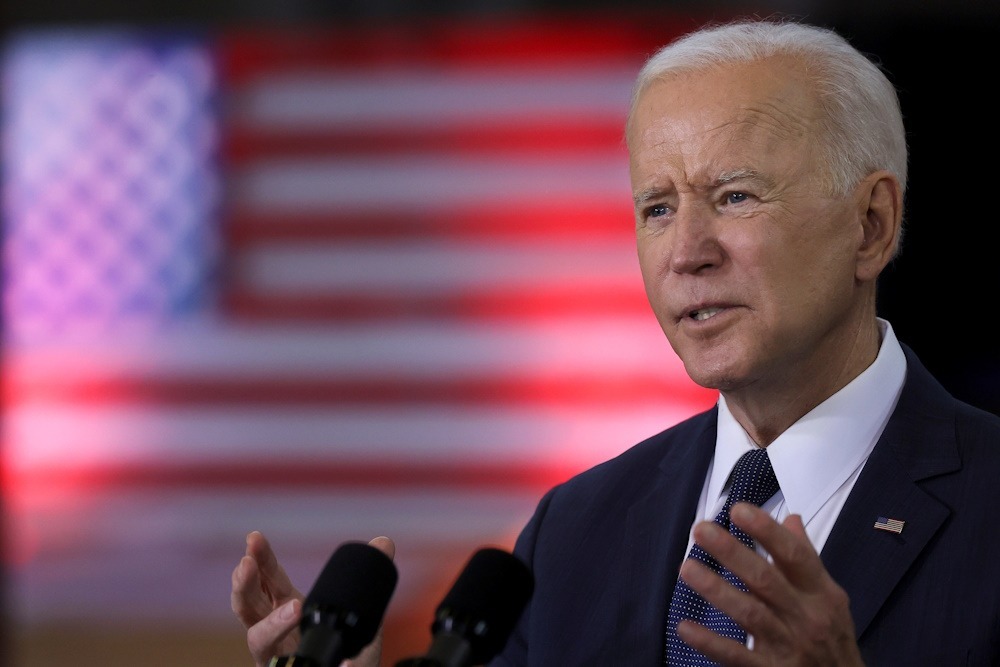

KKR, Blackstone, and Whirlpool Fall Victims of Biden’s 15% Corporate Minimum Tax

Companies with low tax rates and significant earnings would be subject to a new levy that the Biden administration is planning to expand. In its first year, power provider Duke Energy, appliance maker Whirlpool, and investment firms KKR and Blackstone were all struck hard by President Biden’s 15% corporate alternative minimum tax. Now, the president is looking to increase the levy.

In 2022, Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act in an effort to curb instances when corporations would declare enormous profits to investors while really paying very little in taxes due to the use of legitimate credits and deductions. It was a policy and political issue that Congress had contributed to, and Biden and the Democrats sought to address it by imposing yet another tax.

Companies that have averaged $1 billion in financial-statement earnings over the past three years are intended to be shielded from taxes by the 15% corporate alternative minimum tax, or CAMT. The law ensured that big corporations would pay at least the minimum tax by requiring them to determine their taxable income using both the ordinary system and CAMT, and then paying the higher amount.

Furthermore, its porosity is purposeful. Companies were given the opportunity by Congress to use tax advantages including accelerated depreciation and renewable energy tax credits to offset both the CAMT and the ordinary corporate income tax. As a result, it is still possible for certain successful businesses to pay extremely low tax rates.

Kyle Pomerleau, a senior scholar at the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute, stated that the current structure does not guarantee that corporations will be subjected to the 15% minimum tax rate. That was anticipated when it passed, but it will fail to do that.

With Biden’s proposed rate increase to 21% effective this year and major corporation tax rate increase to 28% from 21%, CAMT—pronounced CAM-tee or cam-TEE in tax circles—is projected to generate an additional $137 billion, bringing the total anticipated revenue for the program to $222 billion over ten years. In a statement, the Treasury Department characterized the CAMT extension as “a targeted approach to ensure that the most aggressive corporate tax avoiders bear meaningful federal income tax liabilities.”

The complicated CAMT is based on income from financial statements rather than regular taxable income, and the government has not yet offered the specific regulations that businesses will need to determine their tax liability, even though it went into force for many in January 2023.

In the absence of these regulations, businesses and accountants are making do with educated guesses for the first year, with complicated and uniquely theirs outcomes. On Monday, a Treasury official stated that it was premature to determine if CAMT was meeting revenue projections or the exact number of corporations that have paid.

In their securities filings, over a dozen corporations have acknowledged or indicated that they will pay their 2023 CAMT balance. The reports given to investors usually don’t elaborate on the specific reasons behind any company’s minimal tax payments, and they cover a wide range of industries.

The CAMT liability for Whirlpool was $28 million, while for Ally Financial it was $128 million. According to Duke Energy, the combination between CAMT and previous international tax credits resulted in a $69 million cost.

Accurate figures were not supplied by KKR and Blackstone. In addition to NVR, Corebridge Financial, General Electric, Airbnb, and Devon Energy have all disclosed CAMT expenses or possible impacts.

Companies often tell investors that CAMT has no influence on their bottom lines, even though it will have those implications in 2023. In the event that businesses reevaluate their tax situation and determine that the normal corporate tax is more onerous, they can utilize the funds from the first year’s CAMT payments to reduce their regular tax liability in subsequent years.

To account for this potential gain in the future, businesses often record larger cash tax payments now and establish deferred tax assets. In most cases, they balance each other out on income statements. Companies, especially those that dip in and out of CAMT, will see their future tax payments accelerated under the new law.

Principal Monisha Santamaria of KPMG’s Washington national tax office observed that when CAMT solely affects cash flow, the level of worry among C-suite executives appears to be much lower.

Some businesses may have CAMT due in 2023 for reasons given by accountants and tax specialists. One major issue is stock-based pay, which causes a misalignment between the company’s tax deductions and its financial statement deductions. If a company books a large amount of income overseas at a rate of 10.5% or takes advantage of a tax reduction for exports at a rate of 13.125%, it may also be subject to CAMT.

Tax policy analyst Kristen Siegele of the Edison Electric Institute, a trade association for utility companies, said that corporations are being driven into the CAMT by a number of factors, including extraordinary sales, unrealized gains, and the laws pertaining to repairs. She added that while the majority of EEI members are exempt from the levy, the largest ones, who account for 75% of clients, may be. Electricity tariffs are a common way for regulated utilities to transfer the expense of taxes on to consumers.

Companies close to the $1 billion three-year average threshold, which decides if the tax is applied at all, experience the most challenging CAMT issues, according to Santamaria. In order to ascertain if payment is necessary, those “scope bubble” businesses must perform a number of intricate computations.

She remarked that it was astonishing to her to see who paid and who didn’t.

The impending tax issue that Congress is attempting to resolve is one factor preventing corporations from participating in CAMT at the moment, according to Ernst & Young’s Colleen O’Neill. For tax reasons, businesses cannot take immediate write-offs for research expenses; instead, they must spread them out. This will temporarily lower their vulnerability to the minimum tax by increasing their cash tax payments in the ordinary tax system. More corporations would pay CAMT if Congress addressed the issue. A bipartisan bill with strong corporate backing has cleared the House but is stuck in the Senate.

Companies are unable to engage in extensive tax planning to evade the CAMT at this time due to a lack of knowledge regarding its operation, particularly in the absence of Treasury regulations.

When it comes to corporate AMT, O’Neill noted that taxpayers are more likely to be on defensive than offense. They may halt what they’re doing if they fear it could expose them to liability.