The 9-month-old AI startup challenging Silicon Valley’s giants

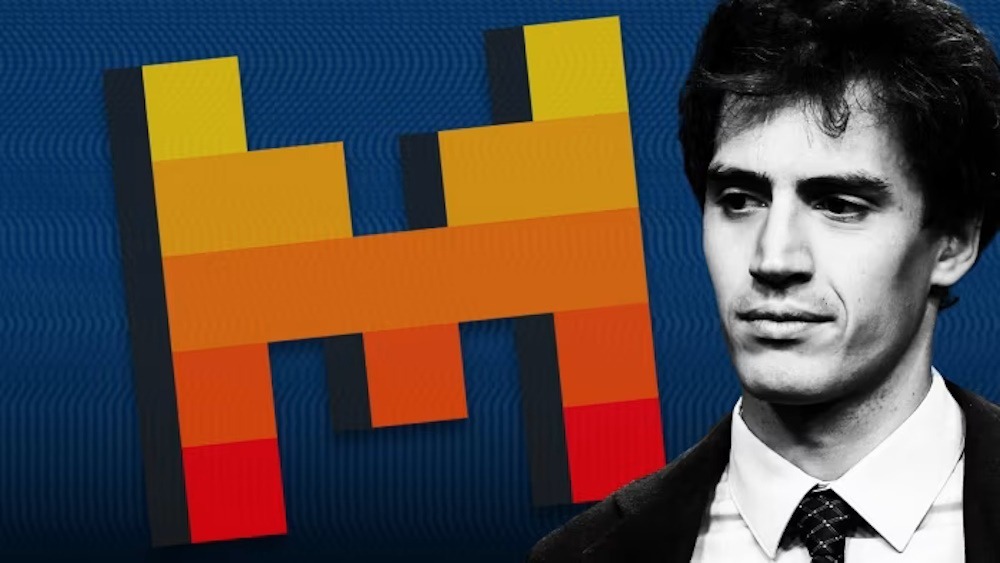

This time last year, Arthur Mensch was 30, still employed at a Google unit here, and artificial intelligence had just started to take off in the public consciousness as something more than science fiction.

Since then, so-called generative AI that can converse—and possibly reason—like humans has become the most talked-about technology breakthrough in decades. And the startup Mensch left Google to launch, now all of nine months old, is valued at slightly more than $2 billion.

The velocity of change reflects the frenzy—and fear—that surrounds the efforts to build and commercialize advanced AI systems.

Mensch’s startup, called Mistral AI, is challenging the conventional wisdom that the winners of the AI race will emerge from among the tech industry’s U.S. giants. Mensch, who founded the company with two engineering-school friends, doesn’t think enormous scale is essential—or that the U.S. will necessarily dominate.

“I’ve always regretted that there was no Big Tech in Europe,” Mensch, 31, said at Mistral AI’s Paris office. “I think this is our chance to become one.”

Mensch’s company, which has raised just over $500 million from investors including Andreessen Horowitz, remains tiny compared with the Goliaths of the industry.

Microsoft-backed OpenAI and Alphabet’s Google are pouring billions of dollars into training the latest AI systems, leveraging their access to the specialized computer chips needed to build such systems and the fat balance sheets needed to pay for the electricity those chips consume.

Mistral, named for a strong wind that blows from France, is founded in part on the idea that a lot of that money is being wasted.

Mensch, who started in academia, has spent much of his life figuring out how to make AI and machine-learning systems more efficient. Early last year, he joined forces with co-founders Timothée Lacroix, 32, and Guillaume Lample, 33, who were then at Meta Platforms’ artificial-intelligence lab in Paris.

Together, they are betting their small team can outmaneuver Silicon Valley titans by finding more efficient ways to build and deploy AI systems. And they want to do it in part by giving away many of their AI systems as open-source software.

“We want to be the most capital-efficient company in the world of AI,” Mensch said. “That’s the reason we exist.”

On Monday, Mistral plans to announce a new AI model, called Mistral Large, that Mensch said can perform some reasoning tasks comparably with GPT-4, OpenAI’s most advanced language model to date, and Gemini Ultra, Google’s new model.

Mensch said his new model cost less than €20 million, the equivalent of roughly $22 million, to train. By contrast OpenAI Chief Executive Sam Altman said last year after the release of GPT-4 that training his company’s biggest models cost “much more than” $50 million to $100 million.

The industry is taking note. Mistral has attracted interest from corporate clients and investors including Microsoft, which on Monday plans to announce that it is adding Mistral’s new model as an option for developers on its Azure cloud service. As part of the deal, Microsoft will take a small stake in the company.

Mistral has also partnered with and sold small stakes to other companies including enterprise-software company Salesforce and Nvidia, maker of the most powerful graphics processing units, or GPUs, used to build AI systems like Mistral’s.

Brave Software made a free, open-source model from Mistral the default to power its web-browser chatbot, said Brian Bondy, Brave’s co-founder and chief technology officer. He said the company finds the quality comparable with proprietary models, and Mistral’s open-source approach also lets Brave control the model locally.

Eric Boyd, corporate vice president of Microsoft’s AI platform, said Mistral presents an intriguing test of how far clever engineering can push AI systems. “So where else can you go?” he asked. “That remains to be seen.”

Tall, with a thick nest of dark hair, Mensch doesn’t look or act the part of a tech geek CEO. Friends and colleagues say he is quick with a joke over a beer. Also an athlete, he finished the Paris marathon in less than 3½ hours months before wrapping up his doctoral thesis in 2018.

Mensch has long been pulled between academic pursuits and entrepreneurial ones. He grew up in the suburbs west of Paris, the son of a physics teacher mother and a father with a small tech business.

The future CEO attended some of France’s top schools for mathematics and machine learning. His advisers described a student who jumped eagerly into projects and mastered them even if he had little background.

“I do like new experiences,” Mensch said. “I get bored very fast.”

A through-line has been trying to make things more efficient. For his doctorate, Mensch worked on ways to scale up software for analyzing three-dimensional brain images from a functional magnetic-resonance-imaging system so that it could ingest millions of images—mapping networks of the brain responsible for things like math and faces.

Mensch joined the Google AI unit then called DeepMind in late 2020, where he worked on the team building so-called large language models, the type of AI system that would later power ChatGPT.

By 2022, he was one of the lead authors of a paper about a new AI model called Chinchilla, which changed the field’s understanding of the relationship among the size of an AI model, how much data is used to build it and how well it performs, known as AI scaling laws.

“Who better to challenge the world’s understanding of scaling laws than one of the people who helped define them,” said Sarah Guo, an early investor in Mistral through her venture-capital firm, Conviction.

As the AI race heated up in 2022, Mensch said he was disappointed that big, private AI labs started publishing fewer papers about large language models, sharing less with the wider research community. Once ChatGPT launched, there was a race within Google to match it. Mensch said he went from working on a team of 10 people to 30, and then 70.

“I think I left just before it got too bureaucratic for me,” Mensch said. “I didn’t want to build opaque technology from within big tech.”

Mistral’s initial pitch document to investors last spring decried an “oligopoly shaping up” led by U.S. companies that sold proprietary models.

Early on, Mensch took a role lobbying French policymakers, including French President Emmanuel Macron, against certain elements of the European Union’s new AI Act, which Mensch warned could slow down companies and would in his view do nothing to make AI safer.

After changes to the text in Brussels, it will be a manageable burden for Mistral, Mensch says, even if he thinks the law should have remained focused on how AI is used rather than also regulating the underlying technology.

For Mensch and his co-founders, releasing their initial AI systems as open source that anyone could use or adapt free of charge was an important principle. It was also a way to get noticed by developers and potential clients eager for more control over the AI they use. Mistral’s most advanced models, including the one announced Monday, aren’t available open source.

“It’s obviously a thin balance between building a business model and sticking to our open source values,” Mensch said. “We want to invent new things, new architectures, and we still want to have something to sell extra to our customers.”