Price guarantees are common at art auctions

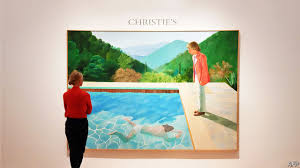

“LADIES AND gentlemen”—the auctioneer scans the room one last time—“the Hockney is sold!” The hammer comes down at $ 90.3m (including fees). Last month a pool scene by David Hockney, a British painter (pictured), set a new auction record for a work by a living artist. What made it an even bigger splash was that it was sold “naked”: that is, without a minimum price or sale guarantee. It may be one of the last great auction nudes.

Many sellers of fine art are promised a minimum sale price, however the auction turns out. They are unnerved by cautionary flops, like Francis Bacon’s “Study of Red Pope”, which was estimated to fetch £60m-80m ($ 80m-105m) in 2017, but failed to sell. Guarantees are most useful for post-war and contemporary works, where the value is most speculative. Last month two-thirds of sales at the “evening” auctions—the highest-profile ones—in New York at Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips, the three biggest auction houses, were guaranteed. The estimated value of those guarantees was at least $ 537m, more than two-fifths higher than in the same month last year, estimates ArtTactic, an arts consultancy.

Auction houses used to offer guarantees themselves. But when the market turned in 2009, after the financial crisis, Christie’s and Sotheby’s had to pay out $ 200m for unsold works. Since then they have moved some risk to third parties, who place an “irrevocable bid” at a predetermined price. If there is no higher bid, the guarantor wins the auction; if there is, the guarantor takes a share of the price above the agreed bid.

Guarantees mean buyers are lured by early interest in the piece. Sellers are reassured that there is no risk of a no-sale, which could depress a work’s future value. Auction houses like them, because they help snare trophy works. But they can also distort auctions. Anonymous guarantors are in a privileged position compared with other bidders in the room, who know only that there is a guarantee but not who has made it, or how much it is. If enough leave what they see as a tilted playing field, the auction ends up being a “private sale in public”, with a single bidder. Since it may never be known if the buyer was the guarantor, and hence if the stated price was the true one, price records become blurred.

The upside for guarantors can be eye-watering. Leonardo da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi”, which sold for a record-breaking $ 450m in 2017 and was guaranteed for over $ 100m, left the guarantor with an estimated $ 90m-150m, according to Bloomberg. And new financial products make such returns more accessible. Pi-eX, an art-investment adviser, makes it possible to buy fractions of guarantees through tradable futures contracts.

The chance to gain a large slice of a dizzy sale price is attracting inexperienced investors, says Anders Petterson of ArtTactic. But it is an unusually risky punt. Some will make enough to hang up their hats for good. Others will be hanging nothing but an unwanted—if masterly—painting.

This article appeared in the Finance and economics section of the print edition under the headline “A bigger picture”