Why Venture Capital Is No Longer a ‘Lifecycle Business’

This article originally ran in Term Sheet, Fortune’s newsletter about deals and dealmakers. Sign up here.

Venture capitalist Ashmeet Sidana believes that some of the best Silicon Valley companies owe their success to a technical insight.

After parting ways with Foundation Capital in 2013, Sidana decided to try out a new investing strategy — back founders taking technical risk, not market risk.

His firm, Engineering Capital, leads seed rounds in companies solving technical problems in the software and core IT infrastructure space. He raised $ 32 million for his first fund, and $ 50 million for his second, which he just began investing out of in Q2 of 2018.

“Most venture firms focus on market risk,” Sidana said. “In other words, they’re good at sussing out when a company has traction, and when it makes sense to invest in that opportunity. Whereas what I’m doing now is the exact opposite of that. The thinking is, ‘We know that people would love this if, and only if, someone had a way of solving this problem technically.”

Engineering Capital typically provides the first institutional money in a company, and its investments include Rubrik, Menlo Security, Prismo Systems, Palerra (acquired by Oracle), and Netsil (acquired by Nutanix).

Sidana spoke with Term Sheet about what it means to have a technical insight, navigating the imbalanced market forces in the seed market, and why he believes venture is no longer a lifecycle business.

TERM SHEET: What are some of the specific characteristics you look for in a founder and company before investing?

SIDANA: I look for the following key elements. First, a technical insight. Every company claims to be a technology company, so I’m talking about a particular subset of that, which is what I define as a “technical insight.” By my definition, Google would fall into that category, but Facebook would not.

Second, I’m looking for a business problem which can be solved in a highly-capital efficient way. In my case, these are all software companies, where a team of five to seven people can build a product and bring it all the way to revenue within the seed stage itself. This is unusual in the enterprise space. I believe that a very small, technically-astute, business-savvy team can actually build an enterprise product with a seed round of financing. From a venture strategy perspective, I have bet heavily on this capital-efficient stage of the company.

How can a founder evaluate whether they have a valuable technical insight?

SIDANA: A technical insight by itself is not valuable. It is not sufficient to build a company. It becomes valuable if it enables a solution to a business problem for a customer, and ideally a lot of customers. For example, the original VMware technical insight was how to build a virtual machine for the x86. When I was running VMware ESX Server, we noticed that customers wanted to keep running their old, primarily Windows NT applications, but on new hardware. Using VMware ESX to consolidate these old servers created an immediate return on investment — which became the genesis of the massive business VMware has today. The reason technical insights are so important is that if a solution includes a technical insight, it gives an unfair advantage to a startup. By definition, no one else can do it. It is not the only way, but many massive companies have been built on the back of a technical insight.

We’re seeing early-stage funds shutting down, citing concerns of excessive capital supply & imbalanced market forces in the seed market. As a seed investor, are you seeing some of these dynamics and how are you navigating them?

SIDANA: We saw a tremendous run up in 2015 and 2016, and I was a part of that. I would go so far as to predict that at least half, and potentially three-fourths of the seed funds that have been raised, will not raise their second or third fund.

It’s fashionable to be a VC right now, and we will inevitably have to see a cleanup of this, which will happen because of market forces. That said, venture is a hard business. Venture is very simple but not easy, and people often confuse “simple” and “easy.” A lot of people right now think it’s easy, and they’ll be sadly mistaken.

Meanwhile, we’re seeing the emergence of mega-funds. The strategy behind Softbank’s mammoth $ 100 billion Vision Fund is to identify a market leader, pour hundreds of millions of dollars in it, and remove the constraint of capital. What is your view on that playbook?

SIDANA: I think it’s brilliant. It’s a thoughtful attempt at taking advantage of a gap in the market. I mean, there is no other Softbank. You can name many other alternatives to my fund, you can even name alternatives to Sequoia and Greylock, but there is no alternative to Softbank. There is no one else who can write checks of that size along with that type of risk appetite and willingness to bend the rules in their favor in a way that Softbank has. And I think it will succeed. I am not pessimistic on Softbank.

How will some of these macro-investing trends, such as VC firms raising mega-funds and venture-backed companies staying private longer, affect early-stage startups in the long-run?

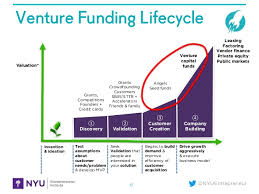

SIDANA: That is the golden question. Venture will change from being a lifecycle business to a stage-specific business. That is one of the fundamental changes that will happen. This will affect the strategy of every firm — whether they’re focused just on seed like Engineering Capital or whether they are traditional investors like Sequoia or Benchmark. By “lifecycle business,” I mean the first institutional investor aims to be the largest non-founder owner and is the lead investor from inception through exit, whether by M&A or IPO. And by “stage-specific,” I mean that the lead institutional investor will change over time, prior to exit.

The great example of this is the battle that was fought between Benchmark and [former Uber CEO] Travis Kalanick with Benchmark subsequently selling and Sequoia buying Uber in simultaneous transactions. In other words, one top-tier firm sold and another one bought, prior to IPO. That was not an accident. It will happen again.

Remember, Benchmark is a firm that had a reputation for being founder friendly — for being one of the best firms on the planet to work with. It blew that entire reputation after it sued one of its CEOs.

[On Aug. 10, 2017 Benchmark sued Kalanick and Uber, alleging that Kalanick concealed “gross mismanagement and other misconduct” while procuring three additional seats on the board.]

SIDANA: In either case, as we now know, eventually Travis gave up disproportionate control, Benchmark sold at a discount, SoftBank became the largest shareholder, and Sequoia bought in simultaneous transactions earlier this year. In other words, a top-tier VC firm sold a portion of their all-time best performing investment at a discount, simultaneously while another top-tier VC firm bought, prior to IPO. This was hard to imagine when venture was a lifecycle business. I believe the days when your first VC became your largest institutional owner and stayed that way all the way through IPO or M&A are gone forever.

Some firms have tried to counter this change in the venture business by raising billion dollar mega-funds or parallel growth funds. From an entrepreneur’s perspective, it is difficult to get attention for a $ 1 million seed investment from a $ 1 billion fund — hence the emergence of specialized seed funds.

Yesterday, Axios reported that VC firm Andreessen Horowitz is changing its fundraising strategy by moving away from multi-stage, multi-sector flagship vehicles. This supports your point that venture is trending toward a more specialized fund approach. Who stands to benefit from this strategy?

SIDANA: The benefit will accrue to whoever can quickly identify their own unique value in this new landscape, and leverage that to enhance their business. So, for example, a VC firm could build a practice with a focus on a particular sector or stage will be served well. This is why I believe Sequoia has separate early stage and growth teams. Or, why Emergence has always had a SaaS focus.

Founders who recognize that all money is not equal — different firms bring different value — will benefit if they choose their investor partners keeping this in mind. They will also benefit because such focused firms and teams will bring more value than just money to them.

Venture has evolved into a big enough market, startups now take long enough, and need so much capital to IPO, that it supports standalone funds, and even standalone firms focused on sub-parts of the overall venture market.

How do you foresee other firms responding?

SIDANA: Great firms will expand and grow to include different offerings. They will become platforms. From my vantage point, it looks like A16Z, Sequoia and Lightspeed are following this strategy. Not a risk to these great firms, but the danger for other firms may be to over-expand and then they will have to find their religion again in order to get back to basics. Some firms will recognize their specialty and stay focused on that. It seems like Benchmark is staying true to its roots and not expanding. Venture is also not a winner-take-all, nor is it a one-size-fits-all market, so I can see many different models being successful.