Illicit financial flows are hard to stop

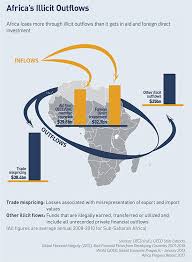

WHEN FOREIGN aid enters developing countries, it is welcomed with handshakes and ribbon-cutting. Private money, by contrast, is sometimes smuggled across borders or siphoned into offshore bank accounts. Everyone agrees that such “illicit financial flows” are a problem. A report published on January 28th by Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a campaign group, estimates that illicit flows to and from developing countries are worth more than a fifth of their total trade with the rich world.

Governments have pledged to plug the leaks, including as part of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. If only they could reach agreement on what they are talking about. A few rich countries, notably America, complain that illicit flows are not properly defined. Statisticians are still puzzling over how they can be accurately measured.

Obviously, gun-running and drug-trafficking should count; in 2011 the UN estimated that financial flows linked to transnational organised crime were worth 1.5% of global GDP. Bribes, and the proceeds of unregistered trade in legal goods, such as cigarettes, probably should, too. But broader definitions also fold in tax avoidance, which may not be illegal. The result is hopelessly vague, diverting attention from dirty money to smear legitimate businesses, argues Maya Forstater of the Centre for Global Development, a think-tank in Washington. Tax activists retort that the line between lawful and unlawful acts is often blurry. Developing countries lack resources to pursue complex legal cases, so big firms find it easier to get away with avoidance that should count as evasion.

Measuring illicit flows is even more fraught. One method exploits discrepancies in trade data. The exports that Ghana reports to France, say, should match the imports that France reports from Ghana. In practice, that is rarely the case. Traders may understate the value of exports, or overstate the value of imports, as a way of slipping money out of a country. They may also fiddle paperwork to dodge border taxes. Big inconsistencies hint at wrongdoing.

GFI combines this method with balance-of-payments data. In 2015 the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa, a group chaired by Thabo Mbeki, a former South African president, used a similar approach to conclude that a net $ 50bn leaks out of the continent each year.

Both figures have been questioned. Some trade discrepancies are indeed caused by fraud, which is why misreporting is less of a problem where corruption is lower or accounting standards are higher. Yet they may also result from errors, quirks or transit trade. One UNCTAD report concluded that almost all South Africa’s gold leaves the country unreported, only for tax officials to point out that most of it was recorded, just in a different format.

A recent report by the World Customs Organisation concludes that existing methods are simply too unreliable to measure the scale of illicit flows. And anyway, trade data capture only one type of malfeasance (smugglers fly completely under the radar). Some experts take a different tack. Alex Cobham of the Tax Justice Network and Petr Jansky of Charles University, Prague, propose two indicators: one based on mismatches between where multinationals report their profits and where their real activity occurs, and another that is a measure of undeclared offshore assets.

Perhaps it would be simpler to abandon the catch-all term “illicit financial flows”. But its very vagueness is the reason it caught on. Rich countries like talking about corruption, which they blame on poor-country elites. Poor countries like talking about tax avoidance, which they blame on foreign multinationals. Loose language keeps everyone happy.

Except the unfortunate statisticians. A team of them from the UN is due to publish some first thoughts this year; it may be several years before an indicator is agreed on. In the meantime, it would be a shame if disagreements distract from action. Beefing up customs authorities, establishing public registries of beneficial ownership and exchanging more information between countries about the taxes citizens and companies pay could all reduce skulduggery—however it is measured.