America’s Treasury refrains from naming any currency manipulators

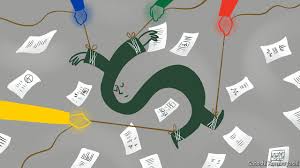

MOST governments are happy when foreigners want their bonds, especially when those foreigners are long-term holders, like central banks. But America is different. It worries that some foreign governments buy its debt to keep the dollar pricey and their own currencies cheap. This “currency manipulation” gives other countries a competitive edge, raising their own trade surpluses and America’s deficit.

Brad Setser of the Council on Foreign Relations, a think-tank, sees an “arc of intervention” across Thailand, Singapore, Taiwan and South Korea that has slowed the dollar’s decline over the past nine months. America has reportedly persuaded South Korea to forswear currency manipulation in a “side-agreement” to their revised trade deal. And on April 16th President Donald Trump tweeted that “Russia and China are playing the Currency Devaluation game…Not acceptable!”

Get our daily newsletter

Upgrade your inbox and get our Daily Dispatch and Editor’s Picks.

Mr Trump’s tweet was at odds with his Treasury Department’s assessment. Every six months it must tell Congress if any big trading partner is manipulating its currency. (Offending governments are scolded, followed by other chastisements if they do not mend their ways.) But its latest report, published on April 13th, refrained from branding anyone a manipulator.

The report did admonish China for its persistently large trade surplus in goods with America. But Russia was barely mentioned. The recent decline in its currency was, after all, prompted by the Treasury’s decision to strengthen sanctions.

Instead the report paid uncustomary attention to India, pointing out that it has a large trade surplus in goods with America and that its central bank has intervened heavily in currency markets, with net foreign-exchange purchases worth 2.2% of its GDP. It was added to a “monitoring list” of countries warranting closer scrutiny.

The list itself does not bear much scrutiny, however. As well as India, it comprises China, Germany, Japan, South Korea and Switzerland. But India has no overall trade surplus and Germany has no currency of its own to manipulate. The list also ignores Thailand and Singapore, which have intervened over the past year to curb the rise in their currencies, according to Mr Setser.

These oddities are not entirely the Treasury’s fault. It is required to assess a country against three criteria: its trade surplus with America, its current-account surplus with the world and its intervention in currency markets. The first measure makes little sense, point out Fred Bergsten and Joseph Gagnon of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. In today’s global supply chains, countries like Singapore can sell materials to China that end up in products bought by America. Their direct exports to America may seem modest. But their indirect exports, embedded in goods sold by China, may be large.

The Treasury is also required to consider only America’s “major” trading partners. It thus limits its analysis to the largest dozen (plus Switzerland, the 15th-largest). That gives small, interventionist economies a free pass, notes Stephanie Segal of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, another think-tank.

Within these broad limits the report’s authors enjoy substantial discretion. And the Treasury is considering broadening the definition of a “major” trading partner. It thus had leeway to prepare a more rigorous report if it had wished to do so. Instead, says Mr Setser, it wrote this report to be ignored. Perhaps Treasury officials do not want to be drawn into Mr Trump’s tariff tit-for-tat, suggests Mr Gagnon. The report waves the flag (invoking “fair and reciprocal” trade) but fires no bullets. It may be hard to cheapen the dollar, but it is easy to depreciate a report.

This article appeared in the Finance and economics section of the print edition under the headline “Tweeting the dollar down”