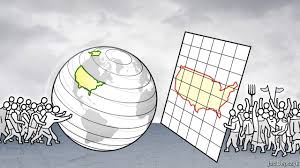

In America, a political coalition in favour of protectionism may be emerging

THE post-war system of global trade has been close to expiring, seemingly, for most of the post-war period. It tottered in the 1980s, when Ronald Reagan muscled trading partners into curbing their exports to America. It wobbled with the end of the fruitless Doha round of trade talks. The system now faces the antediluvian economics of President Donald Trump, who seems bent on its destruction.

Mr Trump’s mercantilism is gaining steam. Straight after saying he would slap hefty tariffs on aluminium and steel imports, he is setting his sights on China, a favourite stump-speech bogeyman. This week he blocked the takeover of an American chipmaker by a Singaporean rival, because of fears of Chinese technological leadership. He is poised to act against China over its theft of intellectual property and its trade surplus.

And yet global trade has proven itself to be remarkably resilient. An optimist could argue that, historically, it is big political realignments that overturn trade-policy regimes, rather than the rogue actions of consensus-bucking presidents. Recent polling suggests many Americans are unenthusiastic about Mr Trump’s steel and aluminium tariffs. The levies have also generated howls of complaint from the business community, which seems likely to persuade Mr Trump to carve out exceptions. The damage he causes could be undone in future. Unfortunately, there is reason to fear the emergence of a new, less liberal consensus.

When discussing trade-policy trade-offs, economists typically focus on conflicts between producers and consumers. They see consumers benefiting from liberal trade rules, enjoying foreign wines and cheap Chinese electronics. But households, they reckon, are rarely animated enough about trade fights to mount serious opposition to producers, who are assumed to favour protection and who are highly motivated and organised in their lobbying for tariffs and other barriers.

Yet in practice, interests diverge across industries and regions. In America, as Douglas Irwin describes in his magisterial history of trade policy, “Clashing over Commerce”, battles between blocs determined trade strategy. Before the civil war Democratic, export-oriented southern states held the political upper hand over the pro-tariff, industrialising states of the north, which tended to vote for the Republican Party and its precursors. The war altered the political balance of power and ushered in an era of industry-supporting protectionism, and Republican dominance, that persisted into the 1930s.

Today’s established policy paradigm has its origin in the early post-war period, when politics strongly favoured liberalisation. Both parties backed expanded trade, for geopolitical reasons and because America’s world-beating export industries faced few competitive threats. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, in operation since 1948, created the environment in which tariffs have tumbled to their present low rates. A scaffolding of treaties, institutions and laws now supports a global economy as interconnected as it has ever been.

That has had two contradictory effects. In some ways globalisation has neutered its potential political opponents. Liberalisation has undercut producers in those sectors most vulnerable to foreign competition, who are also the constituency most in favour of protectionism. Many more jobs, dollars and votes now depend on industries that use steel in production and therefore suffer when it becomes more expensive, than on steelmaking itself. Similarly, liberalisation nurtured the growth of international supply chains, which increased cross-border interdependence and reduced political support for tariffs among firms that are both importers and exporters. NAFTA-bashing elicits cheers at Mr Trump’s speeches, but also causes American firms to leap to the defence of their Canadian and Mexican partners.

In other ways, however, globalisation created the conditions for a significant backlash. In the 1950s and 1960s Americans associated liberalisation with rapid, broad-based economic growth. No longer. Though cosmopolitan Democrats embrace global co-operation and live in cities built on exports of high-value services, concerns about harm to workers and the environment have nudged the party toward a more trade-sceptical position. Elizabeth Warren, a prominent Democrat and senator from Massachusetts, has spoken in favour of tariffs.

More striking is the Republican evolution. Since 2015 Republican voters’ view of trade agreements has flipped from positive to sharply negative. Recent research finds that in congressional districts in which firms had to compete with a larger influx of rival Chinese goods, political support shifted toward more radical candidates overall and, in presidential contests, toward the Republican candidate. Republican policy is shifting in response.

Building blocs

Just as important, the number of industries fed up with China’s overzealous use of its economic power keeps rising. American firms have been forced to sign up to joint ventures with Chinese ones in order to gain access to China’s market. They have lost intellectual property to theft. They face competition from Chinese firms bolstered by state support. Security concerns over new technologies and artificial intelligence further fuel Sino-scepticism in advanced economies.

Political support for an old-fashioned, Trump-style trade war is thin on the ground. Yet a coalition in favour of a showdown with China, made up of both Republicans and Democrats and with the backing of business interests, is all too easy to imagine. The result—a world increasingly divided into rival economic blocs—might well have emerged even without Mr Trump. It will certainly outlast him, too.

This article appeared in the Finance and economics section of the print edition under the headline “Faction and friction”