Trouble in Alibaba spells Huge Returns Call & Put Option Buys

Longtime readers know I’ve been bearish on China for a while now.

Last summer, I warned that China’s currency was poised for a sharp devaluation. In February, I warned that the economic situation in that country was much, much worse than we were being led to believe.

In each instance, I offered up a simple way to profit from the turmoil, thanks to the power of options.

Recently, I set my sights on a specific company in China — one of its largest and most well-known, in fact. I’ve made money betting against it before, and it was time to do it again…

For those who are unfamiliar with the situation in China, let me briefly explain.

Key economic data issued by the government is unreliable at best. The government is desperately trying to create a consumer-driven economy, while simultaneously propping up its real estate sector, stock market and imports.

You can read what I’ve written before about this situation (as well as in other media outlets), so I won’t get into the details. But suffice it to say, risk is high.

Back then, shares dropped 33% — and we made a whopping 69% return in nine days by buying put options. (A put option gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to sell 100 shares of the underlying stock at a specified strike price on the option’s expiration date.)

This time around we needed an even small correction in the stock.

BABA: Overexposed and Fraught With Fakes

Alibaba was founded by Jack Ma in 1999 and became a common name on Wall Street in 2014 after raising a record $ 25 billion from investors during its American IPO.

The company operates online and mobile marketplaces focused on retail and wholesale trade, selling everything from electronics to clothes to cars to an actual airplane.

Its main website, Alibaba.com, looks nearly identical to Amazon.com (NASDAQ: AMZN) but also takes visual and operational cues from eBay (NASDAQ: EBAY) and other large U.S. companies. Alibaba operates two additional sites — Taobao.com, a massive clothing and home goods retailer akin to Target (NYSE: TGT), and Tmall, which offers higher-end clothing and goods.

The company also generates fees from its payment service, Alipay, which offers buyers and sellers a safer, more secure way to transfer funds and buy goods, much like PayPal (NASDAQ: PYPL) does in the United States. The service offers assurances that goods will be delivered on time and as described. The majority of the company’s Alipay profits are generated through transaction fees across its web ecosphere. In addition to its retail business, Alibaba also provides cloud computing (think Amazon’s cloud drive), offers other services and even owns a stake in a leading Chinese soccer team.

Alibaba has positioned itself well, accounting for 75% of all online shopping in China last year. While having this much exposure and control means big profits when consumers are spending and growth is positive, it can be your worst enemy when growth slows and consumers tighten their wallets. And while Alibaba has successfully achieved near full penetration of the Chinese ecommerce market, this also means significant revenue growth is largely dependent on consumers buying more.

To that end, Alibaba and its executives vowed to expand the company internationally, and announced a $ 3.5 billion loan in March, almost certainly for those purposes. However, while international revenues are growing, they’re actually shrinking as a percentage of the company’s overall revenue (down from 9% to 8% year over year).

After a string of questionable and costly acquisitions, the company has only seemed to attract the wrong attention from global regulators.

First, in early 2015, the Chinese government began putting pressure on Alibaba for its sale of fake goods. Although Alibaba seemed to walk away with just a slap on the wrist, regulation could heat up again if foreign pressures increase.

Then, late last year, U.S. trade officials warned Alibaba about its propensity to sell fake, unlicensed goods throughout its ecosystem. And in early May 2016, Alibaba was suspended from the U.S.-based International AntiCounterfeiting Coalition, after just one month as a member.

Founder Jack Ma still doesn’t seem to get it; he basically defended his sales of counterfeit goods, stating, “The fake products today are of better quality and better price than the real names.”

A week later, the SEC launched an investigation to probe BABA’s accounting practices, with results still pending.

Macro Problems and Analyst Weakness

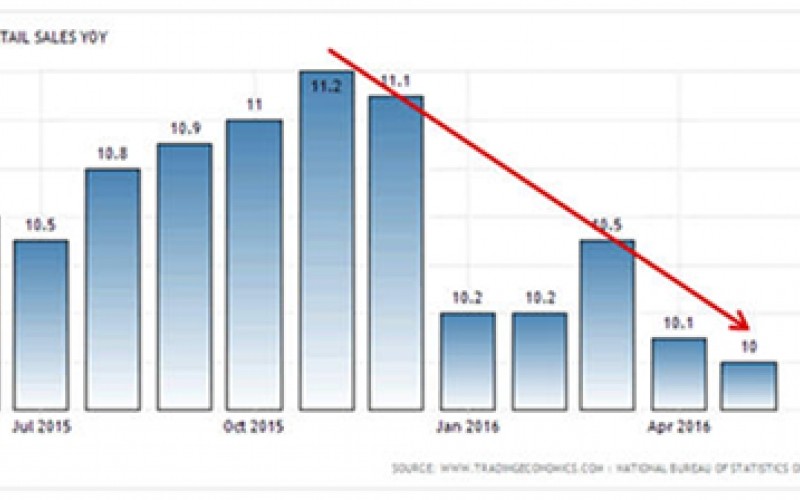

Back at home, Chinese retail sales growth continues to weaken. Growth this quarter has been averaging around 10%, compared to more than 10.5% last year.

The Chinese economy as a whole is also slowing dramatically, and even though the country’s official government numbers put growth at a seven-year low of 6.7%, many believe that figure is much lower, perhaps closer to 4.5%.China’s government is also drowning in dangerous debt, which stands at a whopping 250% of GDP. According to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, one of the country’s top think tanks, these debt loads could be “fatal” and trigger massive, crisis-like ramifications if government revenues slow or if a very possible banking/credit crisis were to take hold. Several prominent U.S. hedge fund managers, including Kyle Bass, are betting on when, not if, the crisis will hit. These are some of the same people who correctly called the U.S. subprime housing collapse, so their outlooks are worth taking seriously.

I think it’s safe to say China’s economy faces serious risks. And whether it’s because of the macro risks, Jack Ma’s reluctance to crack down on counterfeit products or the lack of international expansion and stable earnings growth, analysts are starting to lose confidence in Alibaba.