Janet Yellen may be too modest.

During her press conference, following the Federal Reserve’s decision to raise rates for the first time in a year, she argued that that Fed policy was only “moderately” accommodative—a central banker term for pushing the economy along. That’s despite interest rates sitting below 1% and the Fed’s balance sheet remaining more than four times larger than it was before the financial crisis.

Douglas Ramsey, for one, chief investment officer of The Leuthold Group called this sort of characterization a “shell game,” in a recent presentation to investors, because it belies other statistics that show just how loose the central bank has been. Sure, the Fed’s balance sheet has shrunk modestly this year, and interest rates have risen since the end of the financial crisis. But Ramsey points out that Fed interest rate decisions are not the only factor to look for when determining the degree of accommodation provided. It’s the interaction of the Fed, financial markets, and fiscal policy that really drives the economy.

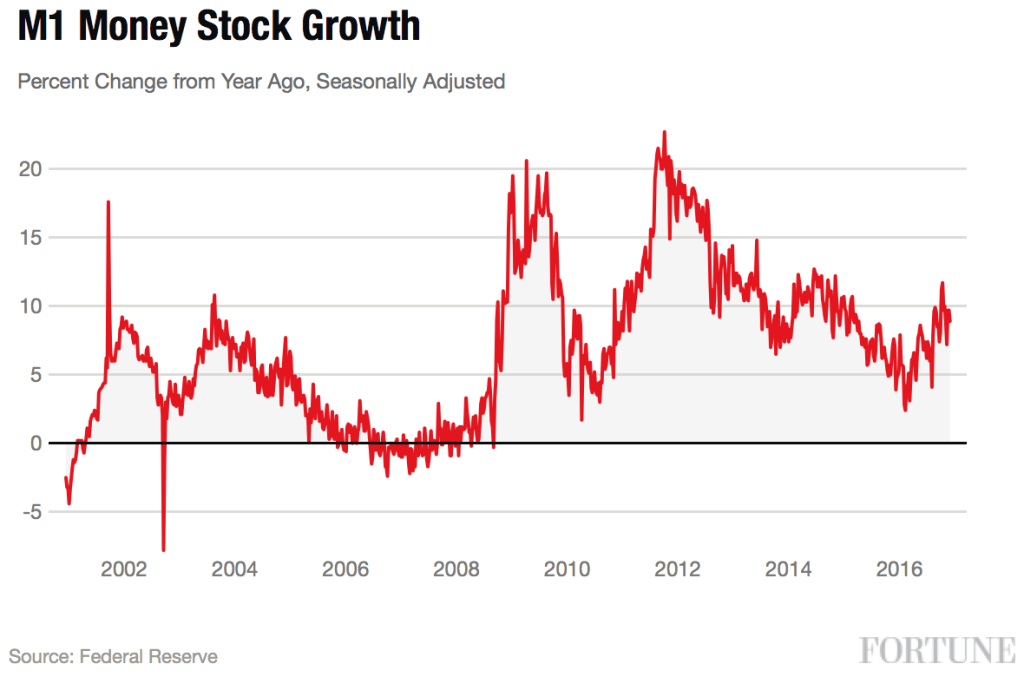

“This year’s solid gains suggest that stocks have finally decoupled from the Fed’s balance sheet,” Ramsey writes. “The absence of [Fed bond buying to drive down rates] and December’s rate hike doesn’t mean that the stock market liquidity is set to dry up.” He argues that we should also be looking at the growth of the money supply, which has accelerated this year. This growth in the money supply suggests some combination of increased bank lending and consumer willingness to keep their assets in ready-to-use cash. That this is occurring even as the Fed is shrinking its balance sheet is evidence that central bank policy may be more accommodative, and potentially inflationary, than some observers believe.

What’s more, this growth in the money supply is occurring at the same time that government debt is increasing faster again as well. “Thus, while Yellen is talking tougher than ever before (which is not so tough at all), policy makers appear to have no intention of imposing a ‘cold turkey’ end to the stimulus,” Ramsey writes.

Throw Donald Trump into the mix, and we may have a real problem. The president-elect has promised a mix of tax cuts and spending increases that would explode the deficit if enacted and impose inflationary pressures on the U.S. economy. The policies would also boost growth, at least temporarily. Yellen said during her press conference that while some of her fellow members had taken Trump’s policy proposals into account in their predictions of the future path of interest rates, it was just one of many factors that lead a number of the central bank governors to predict that the Fed is likely to raise interest rates three times next year. The majority had only estimated two hikes back in September.

This dynamic, combined with the fact that wages seem to be on the rise, suggest that inflation could begin climbing faster than the central bank assumes. Another important point to consider is that while the Fed likes to look at the Personal Consumption Expenditures measure, minus expenditures on energy and food, to gauge price increases, other measure of inflation, like the Consumer Price Index, are already showing inflation above the Fed’s 2% goal.

The Fed prefers PCE because it’s a less volatile measure, but that also means that it could be slow in picking up signs of inflation that PCE is missing. And that it, like the Fed, could be behind. The economic outlook depends greatly on how the Trump administration will tax and spend in the New Year, but there is a good chance that Janet Yellen and company will have some catching up to do once those policies are in place.