Once upon a time, it was de rigeur for U.S. politicians to boast of the prowess of the American worker. Donald Trump, in his policies at least, seems to be putting an end to that.

“We need not shrink from the challenge of the global economy,” then-President Bill Clinton said in his 1997 State of the Union Speech, when free trade was a much more popular idea than it is today. “After all, we have the best workers and the best products. In a truly open market, we can out-compete anyone, anywhere on Earth.”

Today, this kind of American exceptionalism is harder to justify. Many politicians have given up on it altogether. Trump gave a hint at the different approach they’d be taking to international economic competition when he met with executives of the heating and cooling firm Carrier. “I don’t want them moving out of the country without consequences,” Trump told the New York Times. Mike Pence added, contra Clinton, that “The free market has been sorting it out and America’s been losing.”

A Republican Vice President arguing that the White House should interfere with the workings of the free market in order to protect American workers would have been unthinkable just five years ago. But there is increasing evidence that global trade doesn’t work the way that free market fundamentalists have always believed.

In a new working paper published on Monday by the National Bureau of Economic Research, economists David Autor, David Dorn, Gordon Hanson, Pian Shu, and Gary Pisano come to the same conclusion. The paper finds that competition with Chinese exporters have had deleterious effects on American innovation. To do so, the authors looked at how import competition affects innovation in the United States by studying the effect of increased import competition on American manufacturing firms’ R&D spending and issuance of patents. “Our results suggest that the China trade shock reduces firm profitability in U.S. manufacturing, leading firms to contract operations along multiple margins of activity, including innovation.”

This is counter to the popular belief that while specific American workers may be harmed by free trade encouraging low-skilled jobs to move abroad, the American economy would benefit overall by increased competition because competition leads to more innovation and lower prices for consumers.

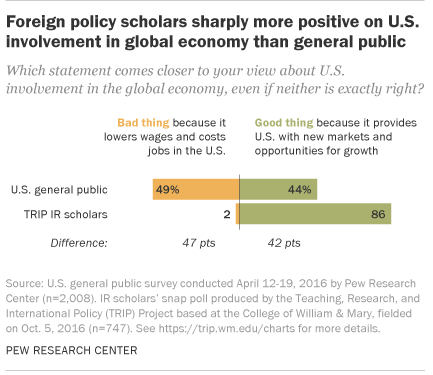

But this economics-101 conception of the global economy has long since stopped working for the American people, and the political class is finally catching on. Last month, the Pew Research Center published two sets of polling results that show that the plurality of Americans believe that “U.S. involvement in the global economy is a bad thing because it lowers wages and costs jobs in the U.S.” However, when scholars in international relations at major Universities were asked the same question, 9-in-10 said that it was a good thing because “it provides the U.S. with new markets and opportunities for growth.”

This likely shows the disconnect between the theoretical foundations of how international trade works and the practical and anecdotal effects of what average people see everyday. In theory, international trade makes everyone richer as countries shift production to goods and services they can produce most efficiently. But this increased wealth is of little consequence to average folks if it captured by the lucky few.

One of the more perceptive observations of the Donald Trump campaign was that the political and academic class in the United States had overlooked these effects, while many Americans have not.