The Upsurge in Electric Vehicle Battery Metals Is About to Collapse

Officials in South Carolina celebrated what they saw as a game-changer when the most valuable lithium business in the world revealed plans for a $1.3 billion factory in the state last year.

South Carolina’s booming electric-vehicle industry relies on Albemarle, a high-tech initiative based in Charlotte, North Carolina, to process various sources of lithium, such as discarded batteries.

The ambitions have been hindered less than a year later due to a decline in the price of battery materials and a slowdown in the rise of electric-vehicle sales in both the United States and China. As part of a corporate-wide effort to save costs, Albemarle has delayed expenditure on the project and has laid off employees. The corporation has also delayed investments in other areas.

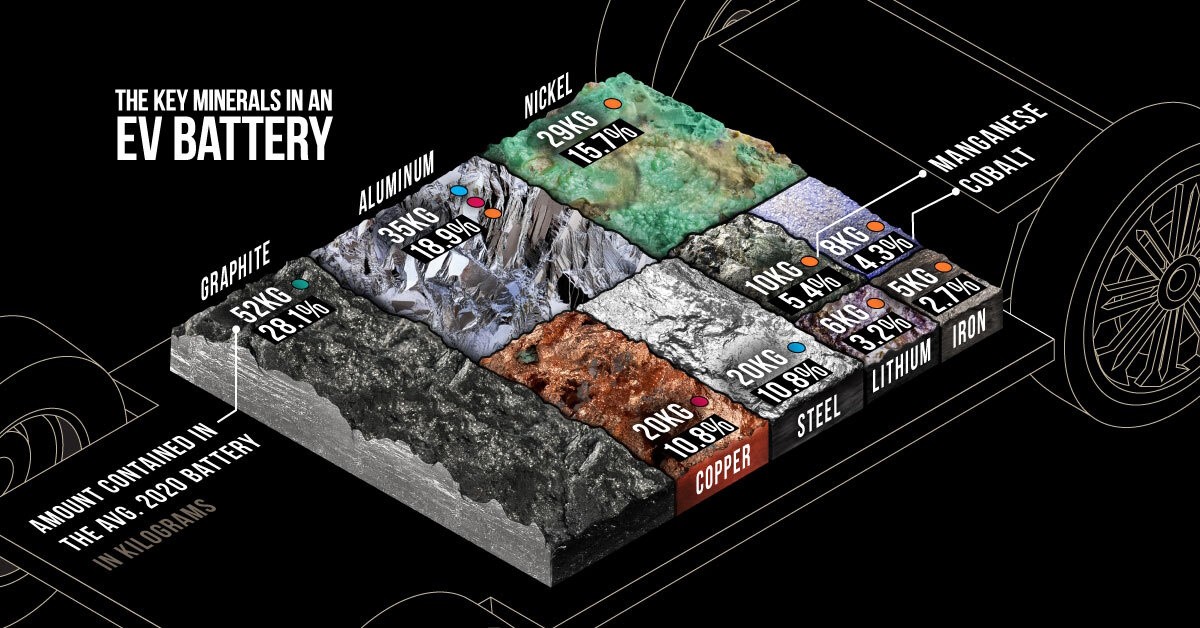

To conserve capital following the excruciatingly rapid decline in commodity prices, producers of nickel and lithium—two ingredients in lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles—have begun halting projects and shutting down mines. Lithium prices have fallen by as much as 90% since January of last year, while nickel prices have fallen by about 50%.

More than 6% of the world’s nickel supply comes from the French island group of New Caledonia in the Pacific, where the unprofitable nickel mine and processing plant is located. Last week, the Swiss mining and trading giant Glencore announced that production will be discontinued at the facility. The corporation has decided to sell its part in the operation due to high operating costs and a weak market.

Shortly after, the most valuable mining company in the world, BHP Group, said that it doesn’t expect the market to rebound quickly and that it may have to temporarily suspend its nickel operations in Australia. Tesla and Ford Motor Company are BHP’s suppliers.

After producers stepped up new projects to feed the global EV industry during a period when sales of the vehicles were losing momentum, the world is suddenly awash with the metals.

Companies including Volvo, Ford, and General Motors are being more cautious and postponing investments in electric vehicles (EVs) due to uncertain consumer demand. In a bankruptcy filing this month, the United Kingdom subsidiary of British electric vehicle manufacturer Arrival cited difficult macroeconomic and commercial circumstances as the reason its products were late to market.

“The nickel situation on a global scale is catastrophic.”

Because of the unpredictability of demand and the lengthy development time required for new mines, metals markets are prone to boom-and-bust cycles.

According to some analysts, the reductions in spending so far have been quite small, which could mean that some miners are still optimistic about demand in the long run.

Although EV adoption is slowing down compared to expectations, the recent dramatic drop in metal prices has the potential to stimulate sales growth for the automotive industry as a whole through the introduction of more affordable models and sales. Once again, automakers are in a state of panic due to the prospect of metal shortages caused by the mining slowdown, which could happen if demand surges too rapidly.

With cash on hand from the recent surge in lithium prices, most major suppliers in the emerging industry have chosen to hold off on halting current operations in favor of postponing future developments.

There have been reports of unprofitable mine closures in the more established nickel business, where miners are claiming they are unable to compete with low-priced shipments from Indonesia. Benchmark Mineral Intelligence reports that over 20% of Australia’s mine supply has been destroyed by the downturn, and that further losses are possible.

Nickel was identified as an essential mineral by Australian officials on Friday, opening the door for corporations to compete for government grants.

China refines over half of the world’s lithium and has led Indonesia’s nickel boom with large investments; some Western officials are worried that the current scenario may halt recent attempts to diversify critical-mineral supply chains away from China. If companies with higher standards are driven out of the market, officials worry that the world would be flooded with metal from cheap but polluted mines.

In a LinkedIn post, Ashley Zumwalt-Forbes, the U.S. Department of Energy’s deputy director for batteries and critical materials, expressed her concern about the worldwide nickel situation, stating that it poses a serious threat to both national and international security, in addition to the environment.

“There is a lack of economics.”

The American lithium behemoth Albemarle was riding high and aggressively expanding until very recently. Currently, compared to a year ago, its share price is 57% lower.

After planning to start building this year, Albemarle’s planned South Carolina factory was to manufacture enough lithium for about 2.4 million electric vehicles per year. The company has not yet announced how long it could delay investing on the project.

A week ago, CEO Kent Masters informed investors that “where prices are today, the economics aren’t there for those projects,” but assured them that the company will keep seeking licenses. He clarified that the South Carolina plant project is being postponed rather than abandoned, even though the firm has halted engineering and construction on the project.

According to Masters, production will decrease and prices will rise if current levels are maintained.

There are lithium producers who are hoping to profit from the current uncertainty. According to CEO Ana Cabral, Sigma Lithium is gaining ground in the Brazilian industry thanks to its cheaper processing costs.

We’re putting money into it. We will continue production even if the market falls further lower. What Cabral meant was that they will still make money, albeit a smaller amount.

Unfortunately, not all nickel miners have that choice. The Australian battery metals manufacturer IGO has stated that it was unable to discover a sustainable solution for its nickel plant in Western Australia, known as Cosmos. By May’s end, it will have shut down that operation.

When a mine isn’t generating anything to sell, the continuing maintenance expenses can reach into the millions of dollars per month, making it a difficult decision for mining executives to mothball the mine.

According to Peter Craig, a contractor from an Australian town known for nickel mining, “Everyone was so excited because [nickel] had found a home” in the batteries required for the electric vehicle boom. He had banked on a continuous boom, which looks less likely now.

We projected nickel’s use over the next quarter of a century and came to this conclusion. “But, you know, these things are impossible to predict,” Craig remarked.