Is This Country Latin America’s Next “Argentina”

One week ago we reported on the economic devastation in he one Latin American country which has yet to be noticed by the broader financial media: Brazil. This is what we said:

Back on December 29 of last year, we explained how under the burden of its soaring current account deficit, and its its first primary fiscal deficit since 1998, not to mention numerous corruption scandals and a dysfunctional monetary policy, the Brazilian economy “just imploded.” We also noted the main reason for the Latin American collapse: Brazil had for the past decade become China’s favorite source of commodities, and now that China suddenly no longer needed commodities, the Brazilian economy went into freefall.

We followed this up a month later with “Brazil’s Economy Is On The Verge Of Total Collapse” which repeated more of the same, only this time the situation was even worse.

It took the rating agencies 7 months to figure out what our readers had known since 2014, when two days ago S&P downgraded Brazil’s credit rating from Stable to Negative citing, what else, the “sharp deterioration of the growth and fiscal consolidation outlook and heightened political/institutional friction” adding that “the negative outlook reflects the agency’s view of a “greater than one–in–three likelihood that the policy correction will face further slippage given fluid political dynamics and that the return to a firmer growth trajectory will take longer than expected.”

Following the S&P announcement others promptly jumped on the bandwagon, most prominently Goldman Sachs which had some jarring words about what is going on in Brazil’s economy:

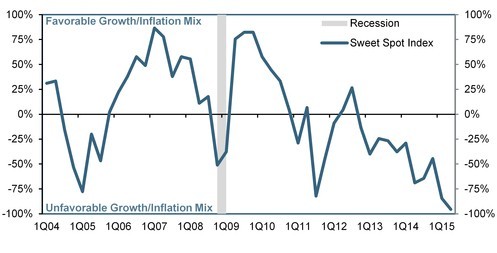

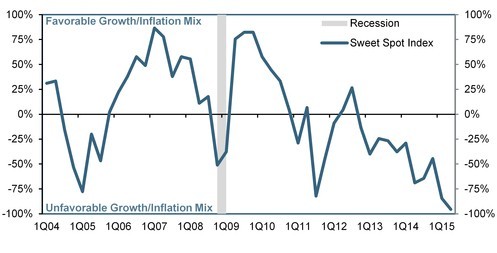

Records show that over the last 11 years we cannot find a period with a strictly-worse growth-inflation outcome than that of 2Q2015 . That is, since 1Q2004 there has not been a single quarter in which we had simultaneously higher inflation and lower growth than during 2Q2015. In fact, in 96% of the 46 quarters between 1Q2004 and 2Q2015 the economy was delivering simultaneously higher growth and lower inflation than during 2Q2015.

We concluded as follows: “In short, the Brazilian economy has never been worse and just to hammer that point home, Goldman added a chart which makes it quite clear that Brazil is not in a recession: it is almost certainly in a depression at this moment – note the recession bar on the chart below and where it is now.”

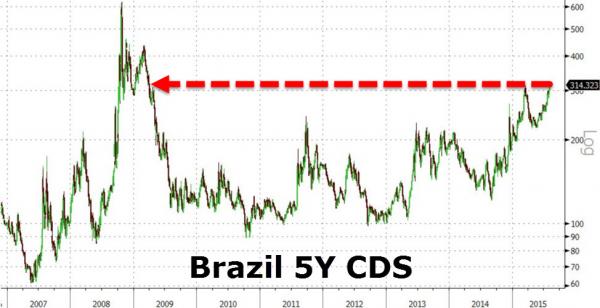

Today, following another spike in negative news, it appears that the credit markets have finally woken up, and a quick look at Brazil’s CDS shows that following today’s spike to 314bps, the country’s implied default risk is back to levels last seen in April of 2009!

And here’s why we expect the blowout in CDS not to stop here.

First, overnight the WSJ reported that Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff’s approval rating has slumped into the single digits to a record low, as the country’s economy struggles and a corruption scandal grows.

Only 8% of respondents across the country said Ms. Rousseff’s administration was “good or excellent,” and 71% considered it to be “bad or terrible,” according to a poll released Thursday by the Datafolha polling institute. That compared with approval of 10% and disapproval of 65% in a June poll, also by Datafolha. The survey result is the lowest for any president since 1990, when the polling series began.

Ms. Rousseff’s approval rating in the latest poll was lower even than former President Fernando Collor de Mello, who slipped to 9% in September 1992, shortly before he was impeached.

As the WSJ adds, Rousseff is facing a combination of negative factors, of which the depressionary economy is just one: “The county’s economy is expected to contract by around 1.8% this year, according to a central bank survey of private sector bank economists. Annual inflation stands at 9.25%, well above the central bank’s tolerance band of 2.5% to 6.5%. And the poor economic conditions are raising fears among Brazilians that they could lose their jobs.”

Then there is corruption:

Meanwhile, a continuing investigation surrounding state-run oil company Petróleo Brasileiro SA, or Petrobras, is also weighing on Ms. Rousseff’s approval rating, though she hasn’t been accused of any wrongdoing and has denied involvement in the scandal. Petrobras has said it is cooperating with the investigation.

Earlier this week, federal police arrested José Dirceu, a former minister of ex-President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, on allegations that he received bribes from former Petrobras executives. A lawyer representing Mr. Dirceu said he denies any wrongdoing.

Mr. da Silva, who handpicked Ms. Rousseff as his party’s candidate to succeed him, hasn’t been implicated in the Petrobras scandal.

Worse, like in Greece, Brazil’s ruling coalition is now fracturing, when yesterday two parties broke from President Dilma Rousseff’s ruling coalition, further eroding support for her measures to shore up the country’s fiscal accounts.

This happened after the lower house approved in a first round vote a constitutional amendment by 445 against 16 votes granting salary increases to police chiefs, prosecutors and government attorneys. The bill still needs to pass a second round vote before going to the Senate.

Earlier, leaders of the Brazilian Labor Party and the Democratic Labor Party, or PTB and PDT, said they would act independently and no longer participate in meetings of the ruling coalition. The parties together have 44 out of 513 seats in the Chamber.

But Brazil’s biggest concern, the one from which all of its other problems stem, is China. Unless the country that was the driver of Brazil’s commodity export golden age returns to its place as Brazil’s most important trading partner, no matter what fiscal or monetary policies Brazil implements, the domestic politics, already ugly, are set to get worse.

And as everyone knows by now, China has its own spate of problems to deal with, with Brazil’s commodity export troubles far on the back burner.

Which is why expect more credit market participants to notice the depressionary developments in brazil, and as the country’s CDS continue to blow out, many will start asking themselves: is Brazil the next Argentina?